The role of women in Peacekeeping Operations (PKOs) as a principal driver of long term peacebuilding and a necessary element of optimal implementation has only recently been acknowledged. The United Nations has since spearheaded initiatives to diversify Peacekeeping Operations across the world, yet the percentages of women participating in these operations still remain strikingly low.

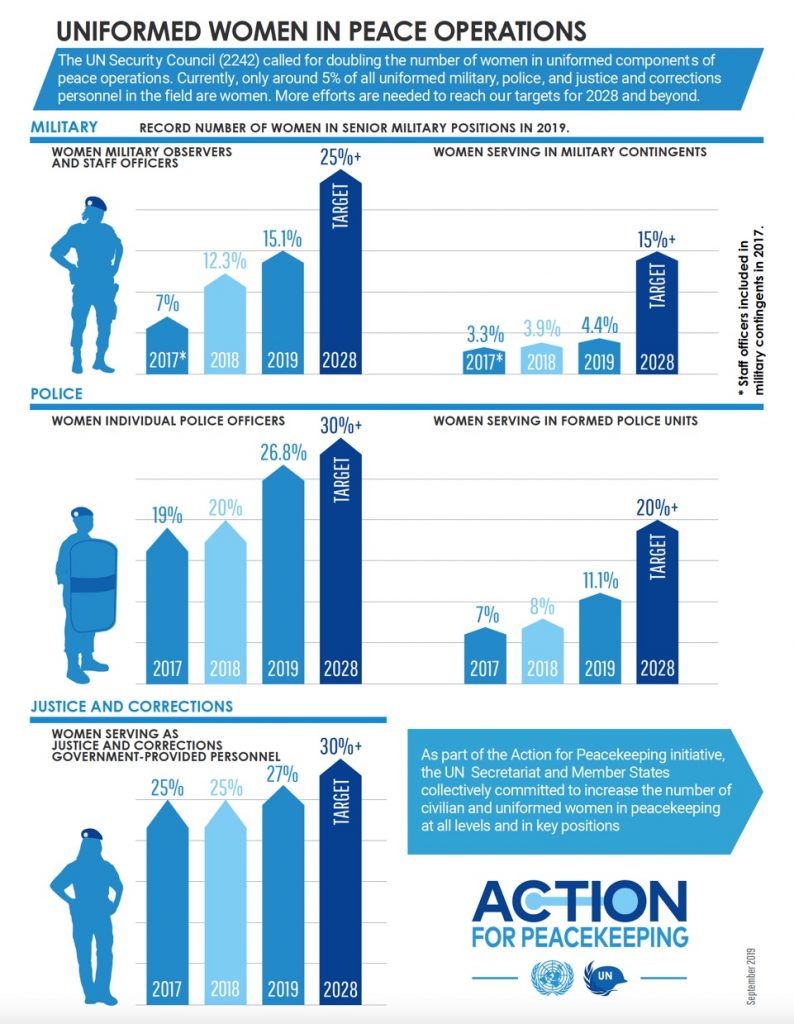

In 1993, women made up 1% of deployed uniformed personnel. In 2019 , out of approximately 100,000 peacekeepers, women constitute 4.4% of military personnel and 11.1% of police personnel in UN Peacekeeping missions

– United Nations Peacekeeping

Why does this disparity persist? Why do expectations of women’s impact in Peacekeeping Operations often differ from the reality on the field? It’s time to understand the underlying dynamics that have been conditioning gender dynamics in peacekeeping, and what to do about them.

Women in peacekeeping: benefits, constraints, and optimization

Generally, the importance of this role is understood along two major lines of argumentation: the instrumentalist rationale centered on possible operational benefits, and the gendered analysis, based on the lessons learned from success cases in equal opportunity peacekeeping efforts and subjacent narratives regarding women’s role in PKOs. The main possible areas of impact that these rationales explore are: interaction with local communities, specifically women and girls; influence on entrenched patriarchal attitudes; encouragement for women from the host community to mobilize; gathering of community-based intelligence; and the prevention, reporting, and mitigation of sexual abuse.

Both rationales state that women’s contributions within these operations hold a multifaceted impact; correlated with increases in the level of security and cooperation with local women, increased trust from the host community, and better civilian-military interaction. These factors correlate positively with PKOs stability in post-conflict societies.

However, there are subjacent issues. Interaction between both parties depends on factors such as identification with the challenges local populations face, trust afforded to the peacekeeping force, the cultural acceptance of the host society of women within this force, a lack of language barriers, and commonalities in racial, ethnic, religious or cultural identities, among others. Thus, we can affirm interaction is highly context-specific and will depend on issues beyond gender to exist. That said, it does also hold a notable gendered dimension, as societal or cultural factors may cause local women and girls to be more inclined to engage with female peacekeepers. This defines the importance of deploying gender-mixed units because it facilitates interaction and gender can be a significant element in certain circumstances.

Notwithstanding the increases of gender awareness training for peacekeeping staff, both pre-deployment and in- mission, few peacekeepers ultimately receive any training on the specific issues conditioning gender relations in their deployment station, and implementation varies extremely by troop-contributing country and mission. This is coherent with the fact that, even when efforts for inclusion are undertaken by increasing women in PKOs, this does not automatically bring forth gender equality in the forces or establish gender mainstreaming as a practice in PKOs. While this may seem obvious, the “add women and stir” dynamic remains pervasive in state policy as a final goal, rather than a step towards effective gender equality.

To actually develop meaningful participation of women in PKO’s, women need to be integrated into senior positions with the capacity to affect decision-making and leadership within the operations, and women peacekeepers must receive training that will allow them to substantially affect and transform the context and development of their missions. Furthermore, as stated by Karim and Beardsley, “the challenges peacekeeping operations face are institutional in nature”, and thus require structural changes to be implemented in conjunction with women’s representation and leadership in order to affect the fundamental power structures of peacekeeping.

Main areas of influence and potential action

The benefits of having more gender-mixed units in peacekeeping cannot be generalized, and the possible impact of women in these missions remains context-specific. When considering the potential impact of including more women in postconflict peacekeeping, it remains important to note both the unique contributions they may provide and the structural and operational constraints that may hinder this differential potential. Furthermore, any contributions must be understood critically, and reference made to experiences of women currently in field operations, so as to not fall back on essentialized conceptions and unrealistic expectations of women’s role in PKOs.

It is worth noting that there is sufficient evidence to affirm that when properly trained, visible, and engaged with the host community, women peacekeepers can provide unique contributions to PKOs based on their gender and enhance operational success. These contributions are only possible if accompanied by training specific to the mission’s host country gender dynamics and needs; as well as progressive structural changes that allow for the breakdown of institutional hindrances to equal opportunity peacekeeping.

Simply recruiting more women remains insufficient to expect changes, and it is fundamental to avoid the “add women and stir” narrative in devising new policies for PKOs. Both the UN and governments should view the further inclusion of women in peacekeeping as a means towards a greater goal; the promotion of gender equality and the integration of nuanced gender mainstreaming policies as natural elements of PKOs. The objective of these policies should always be to better the security of the societies where the mission is deployed and ensure equal opportunity peacekeeping. Gender mainstreaming should contribute, along with structural transformations, to achieving more equal representation, alterations in traditional definitions of peacekeeper identity, and subverting the male-dominated structure of peacekeeping as conditions necessary for the effective inclusion of women in peace operations.

Header Image Credit: UNDPKO

References

Basu, S. (2018). The women in blue helmets: gender, policing, and the UN’s first all- female peacekeeping unit; Equal opportunity peacekeeping: women, peace, and security in post-conflict states.

Dharmapuri, S. (2011). Just add women and stir?. Parameters, 41(1), 56-71

Heinecken, L. (2015). Are Women ‘Really’ Making a Unique Contribution to Peacekeeping?: The Rhetoric and the Reality. Journal of International Peacekeeping, 19(3-4), 227-248.

Karim, S., & Beardsley, K. (2017). Equal opportunity peacekeeping: Women, peace, and security in post-conflict states. Oxford University Press.

Lyytikäinen, M., Popovic, N., Penson, C. N., & Santo Domingo, A. (2007). Gender Training for Peacekeepers: Preliminary overview of United Nations peace support operations. United Nations International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women (UN-INSTRAW).

Mackay, A. (2003). Training the uniforms: gender and peacekeeping operations. Development in practice, 13(2-3), 217-223.

Mazurana, D. (2003). Do women matter in peacekeeping? Women in police, military and civilian peacekeeping. Canadian Woman Studies, 22(2).

Odanović, G. (2010). Participation of women in UN peacekeeping operations. Wester1n Balkans Security Observer, 16, 70-79.

Simic, O. (2013). Moving beyond the numbers: integrating women into peacekeeping operations. Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre Policy Brief.

Valenius, J. (2007). A few kind women: Gender essentialism and Nordic peacekeeping operations. International Peacekeeping, 14(4), 510-523.

IVolunteer International is a 501(c)3 tech-nonprofit registered in the United States with operations worldwide. Using a location-based mobile application, we mobilize volunteers to take action in their local communities. Our vision is creating 7-billion volunteers. We are an internationally recognized nonprofit organization and is also a Civil Society Associated with the United Nations Department of Global Communications. Visit our profiles on Guidestar, Greatnonprofits, and FastForward.