Trafficking, in all its expressions, is a global threat to which no country is immune. The phenomenon has come to be marked by its ever-increasing complexity, and has become a political priority for governments around the world. Often, when looking at trafficking, we center on victim profiles and rehabilitation. But this focus continues to allow only palliative measures. We must look to the characteristics that allow human trafficking to continue to expand year by year: drivers, profits and globalisation.

Human Trafficking as a global phenomenon

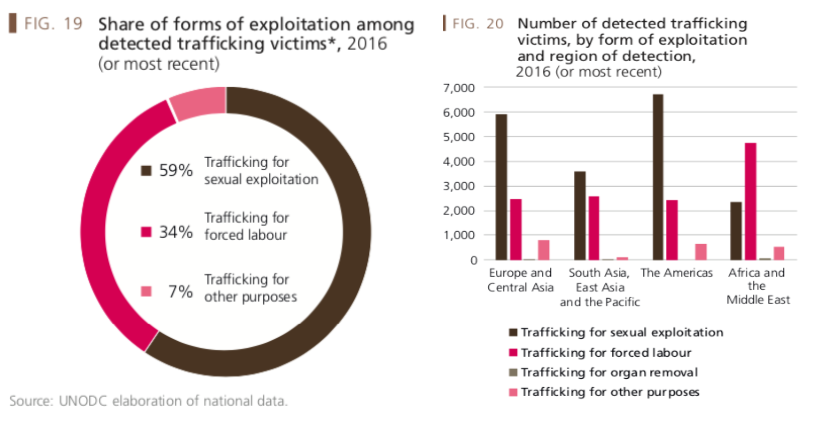

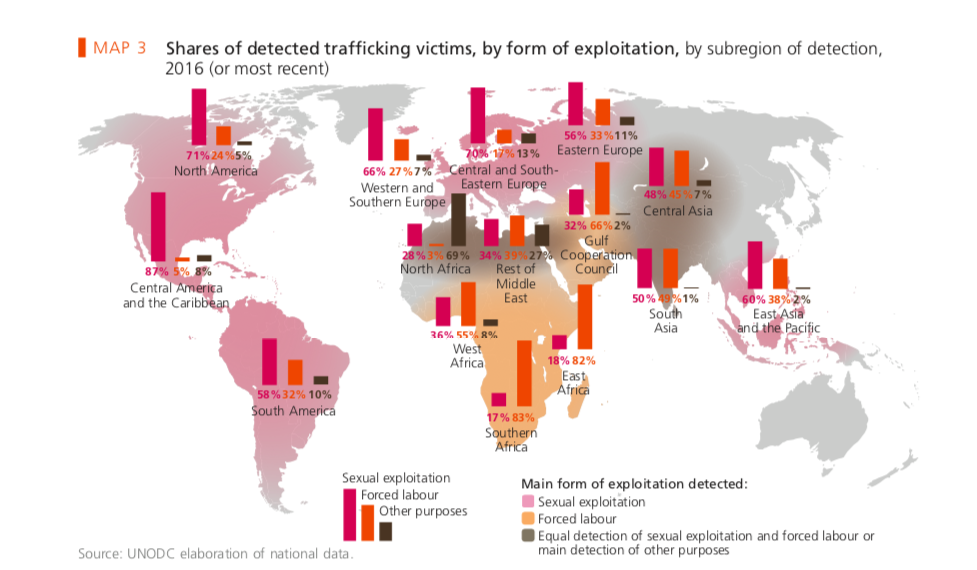

Estimations suggest there are approximately 40.3 million people in modern slavery. The United Nations estimate that women and girls represent 72% of victims of trafficking, and mainly suffer sexual exploitation; while men and boys compose the remaining 28% and are mainly trafficked for forced labor.

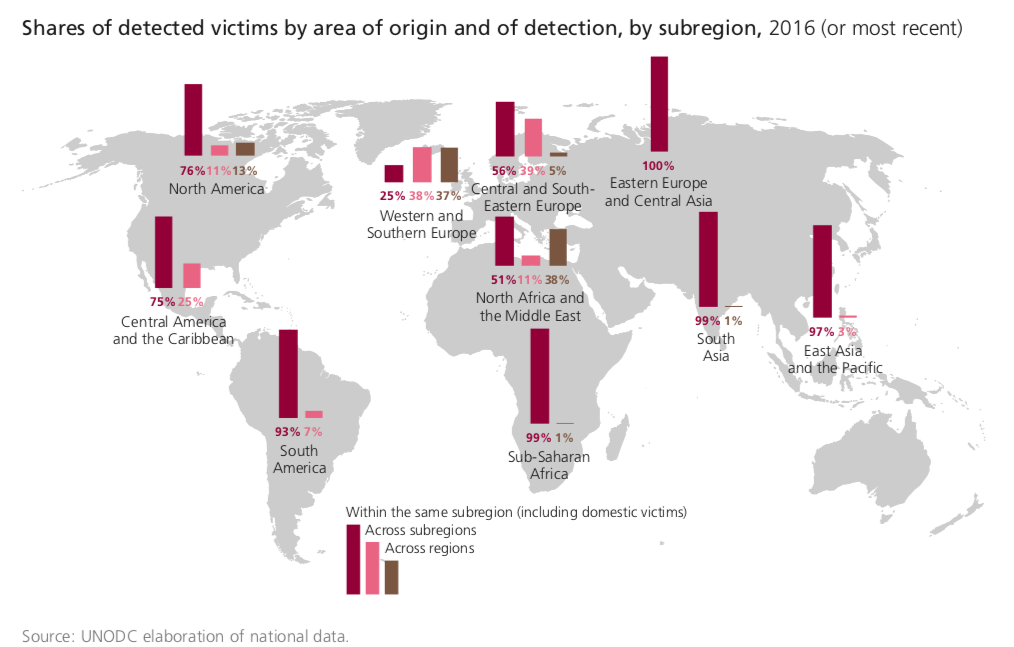

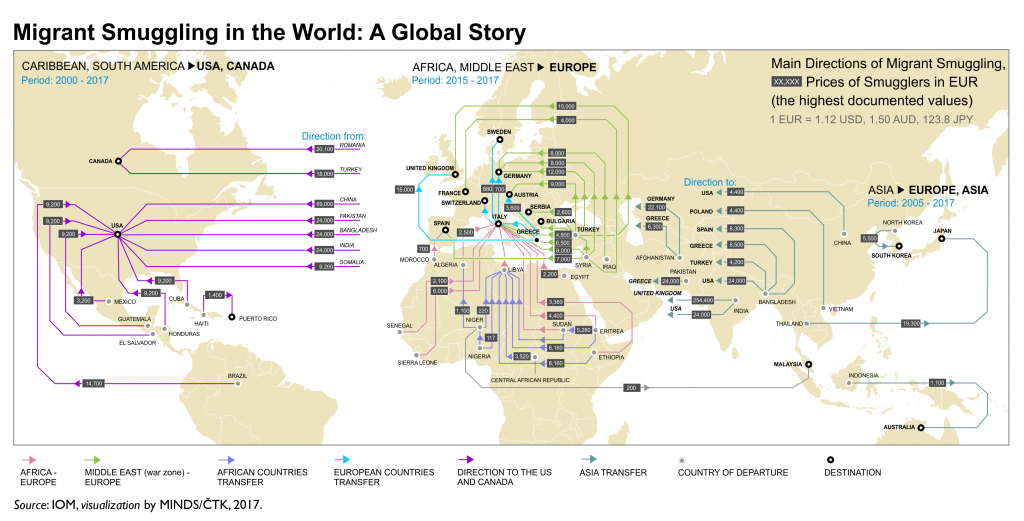

Different regions present separate profiles in terms of victims and predominant forms of exploitation; often being part of a wider flow of trafficking. Thus, we see Western Europe and the United States are defined as regions of destination for victims, while Africa is primarily as a region of origin and transit. Notable is the situation in Southeast Asia, which not only operates both as a region of origin and transit but also as a final destination for trafficking in persons. This is supported by the fact that detected victims reveal patterns in extreme diffusion of trafficking flows, with over 500 routes identified between 2012 and 2014. It is estimated that much of the traffic is intra-regional, although in areas with less police effectiveness the number of reported cases is lower.

Drivers of Human Trafficking

The drivers of human trafficking reflect the politico-economic divisions of the north-south and east-west binary. Its dynamics can be explained through migration theory, which integrates both a political and economic perspective to account for flows of human migration in terms of “push and pull” factors, essentially representing supply and demand drivers. Push and pull factors can be economic, political, and social, among others. These factors are especially vulnerable to armed conflicts and situations of protracted insecurity. Furthermore, areas with weak rule of law, while in peace, may also provide effective impunity to traffickers, encouraging their operations.

Push factors generally put women particularly at risk for trafficking due to issues of gendered violence in conflict, socio-economic gender imbalances, and the feminization of poverty; disproportionately impacting women in conflict and post-conflict. As a result, this phenomenon holds a particularly gendered dimension, defined by the increased vulnerability, violence, and lack of opportunity women and girls face across the globe and evidenced in the mayor prevalence of women and girls as victims of trafficking.

The Trafficking Economy: profits

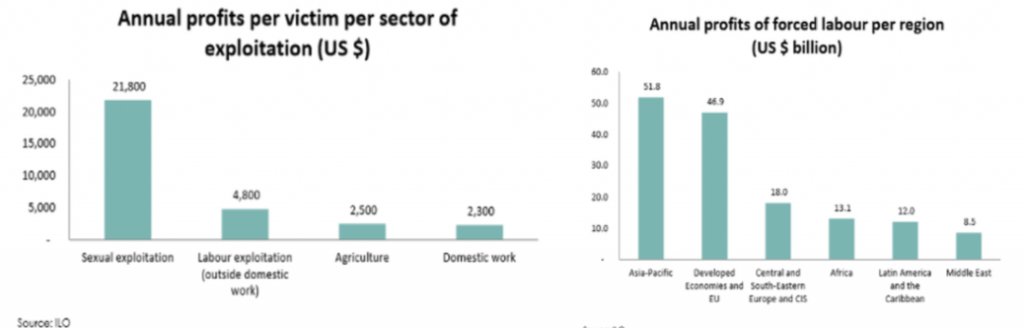

Trafficking in persons generates immense economic benefits for traffickers, which combined with a minimum cost and a low perceived risk of arrest, has grown to define it as an ever-rising market. The ILO estimates that human trafficking globally generates more than 150 billion dollars a year; of which 99 billion dollars derive from sexual exploitation and 51 billion from different forms of forced labor. As a result, sex trafficking stands as one of the most profitable markets in the world.

These figures represent illustrative examples of the exorbitant profit margin derived from sexual exploitation. ILO estimates establish that annual earnings per victim of sexual exploitation are $21,800 per year per victim; far ahead of the profitability of other forms of exploitation such as forced labor.

The effect of globalization

Globalisation has, particularly in the last two decades, become the defining economic reality of the world. This process eliminates restrictions of national borders and interests, generating a tendency towards a mainly regional or global demand and a focus on competitive markets. As such, it drives wealth; however, it also exacerbates inequality as the specialization of certain markets is imposed.

The impacts of globalisation on the trafficking market are reflected in both supply and demand. On the one hand, globalization has exacerbated national economic inequalities, leading low-income groups to have a higher risk of being exploited. It has also increased the supply capacities of traffickers, reducing the cost of mobility, and allowing them to handle aggregate demands with the most vulnerable populations in several countries. This fact is especially reflected in the prevalence and increase of intra-regional traffic. On the other hand, globalisation has also influenced demand, since the integrations of world markets have generated substantial economic growth, leading to greater labor demand; which is also reflected in the increasing number of registered cases of forced labor and prostitution. In addition, we must take into account the rapid development of urbanisation and the increase in cross-border migration.

As a result, human trafficking has been facilitated by economic globalisation; affecting not only traffickers’ operations, but also the probability that final consumers of goods and services are indirectly related to this practice through global supply and logistics chains.

What we can learn: next steps

Trafficking in human beings has been one of the topics of greatest interest in the criminological discourse of international relations for years; combining human rights dynamics with globalisation paradigms, and international law and regulation issues. Thus, it is necessary for states to employ a holistic strategy to combat trafficking. This involves countering its root causes, not just protecting or rescuing its victims. Only a global effort, across lines of power, can truly serve to curb trafficking before it becomes an even greater behemoth.

References

Amiel, A. (2006). Integrating a human rights perspective into the European approach to combating the trafficking of women for sexual exploitation. Buff. Hum. Rts. L. Rev., 12, 5.

CEDAW (2013). General recommendation No. 30 on women in conflict prevention, conflict and post-conflict situations. CEDA W/C/GC/30.

Chinkin, C., & Fernández Rodríguez de Liévana, G. (2018). Special Rapporteur on Trafficking urges human rights approach and integration with the WPS agenda. Retrieved from https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/wps/2018/11/30/special-rapporteur-on-trafficking-urges- human-rights-approach-and-integration-with-the-wps-agenda/

European Court of Auditors. (2017). EU support to fight human trafficking in South/South- East Asia.

Farquet, R., Mattila, H., & Laczko, F. (2005). Human Trafficking: Bibliography by Region. Data and Research on Human Trafficking: A Global Survey, 43(1/2), 301.

Global Slavery Index (2018). The global slavery index 2016. Dalkeith, Australia: Walk Free Foundation.

Hodge, D. R., & Lietz, C. A. (2007). The international sexual trafficking of women and children: A review of the literature. Affilia, 22(2), 163-174.

Human Rights First (2017). Human Trafficking by the Numbers.

ILO (2014) Profits and Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labour.

ILO (2017). Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: Forced Labour and Forced Marriage.

Outshoorn, J. (2005). The political debates on prostitution and trafficking of women. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State and Society, 12(1), 141-155.

Owens, C., Dank, M., Breaux, J., Bañuelos, I., Farrell, A., Pfeffer, R., & McDevitt, J. (2014). Understanding the organization, operation, and victimization process of labor trafficking in the United States. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

UN Office on Drugs and Crime. (2018). Global Report on Trafficking in Persons.

IVolunteer International is a 501(c)3 tech-nonprofit registered in the United States with operations worldwide. Using a location-based mobile application, we mobilize volunteers to take action in their local communities. Our vision is creating 7-billion volunteers. We are an internationally recognized nonprofit organization and is also a Civil Society Associated with the United Nations Department of Global Communications. Visit our profiles on Guidestar, Greatnonprofits, and FastForward.