Having grown up in a conflict-ridden space, I firmly believe that it is important to conceptualize sustainable peace and security by employing a gendered approach to peacebuilding. My motivation for the approach has been multifaceted, stemming from Yakaka Mandara’s grassroots movement in building peace in Nigeria to Marii Hasegawa’s vision of fostering peace worldwide.

These stories greatly inspired me to reflect on the importance of women’s role in political participation, particularly in the peacebuilding processes and conflict resolution. The Secretary General’s report to the Security Council rightly stated that ‘when women actively participate in the peace talks, the agreement result’s in more durable and peaceful resolutions’.

Wherever There Is Conflict, Women Must Be Part of the Solution.

Under-Secretary:

General Michelle Bachelet

In the efforts to recognize and acknowledge this vision, the year 2000 finally led to the creation of the landmark resolution – Women, Peace, and Security 1325, calling for the active participation of women in the peace and security efforts. Now, when I see this landmark resolution in its 22 years of formation and reflect on its impact on the lives of women around the world, I cannot help but question whether the Women, Peace and Security agenda can be called a successful resolution? If so, then why women around the globe are still struggling to be a part of the peace efforts?

Why Are Women Still Excluded from Peace Processes?

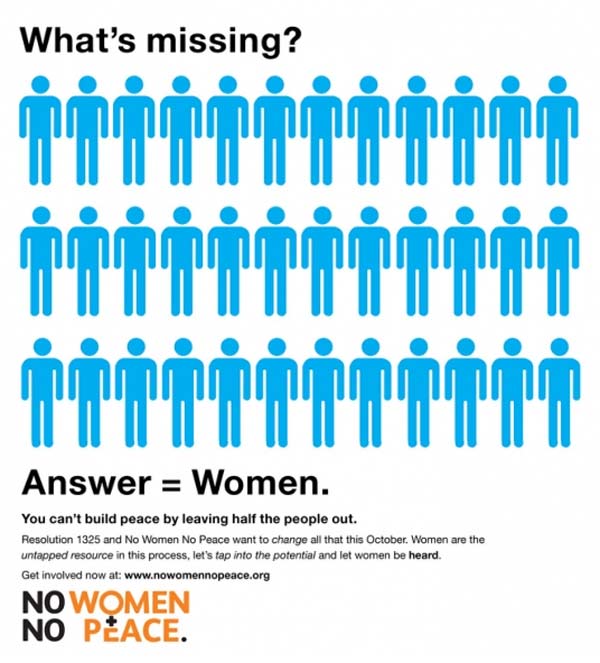

Despite the substantive finding by the research and civil society organizations, showing women’s participation leads to quicker peace results, by and large, women are continued to be excluded in the peacebuilding and security efforts.

Research from the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) ‘Women’s Participation in Peace Processes’ shows that:

- Women’s inclusion in the peacebuilding efforts increases the success of peace agreements lasting for fifteen years by 35%.

- Women groups exercising a strong influence on the peace negotiation process are likely to agree to talks and subsequently reach a peace agreement.

- The presence of female peacekeepers has shown the potential to empower women in their communities by advancing women’s active participation in peacebuilding efforts.

When women participate in peace processes, the resulting agreement is more durable and better implemented.

Krause, Krause, and Branfors

Even with these overwhelming statistics, the peace efforts around the globe have suffered to include women at the peace table. Not going too far, in the year 2020, Libya’s political discussions lead to only 20% of women negotiators, 10% presence of women in the Afghan Talks, and 0% in Yemen’s military talks. This stalled progress of women in peace efforts makes it instrumental for us to dive deeper into the barriers that obstruct women’s participation in the peace process, and understand the – why!

Entrenched Patriarchy and Hegemonic Masculinity

The entrenched patriarchal attitudes, power politics, and gender dynamics of conflict and war continue to impede women’s active participation in the peacebuilding efforts. Violence against women in conflict zones like rape, gender discrimination, and sexual exploitation are labeled as “women’s issues,” thereby excluding them from the peace process. This approach further corroborates the ingrained problem of how masculinity is institutionally entrenched within the peace process.

Annika Kronsell rightly states, “Because such norms are dominant in the institution, they do not require any explicit politics. Masculinity does not need to be thematized. Instead, masculine standards and ideals continue to be reproduced simply through routine maintenance of the institutions.”

Moreover, as members of this deep-rooted patriarchal set up, the onus lies on us to address underlying norms of existing gendered power dynamics and hegemonic masculinity in this challenging authoritarian system.

Institutional and Systematic Exclusion

One of the ground-breaking challenges of the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 is that it fails to address and acknowledge the structural and systematic exclusion of women’s participation in the peace and decision-making process. Furthermore, the criteria of who should be allocated a seat at the table and how their positions are selected for ‘peacemakers’ plays a significant role in understanding this institutional exclusion.

As ‘The Better Peace Tool’ – a guide offering practical steps for the effective inclusion of women peacebuilders states, “The qualification for armed actors is their capacity to wreak violence.” This means that the same so-called peacemakers who are entrusted to sit at the peace tables are the ones responsible for creating conflict. While as Women, Peace and Security activists, policymakers, peace advocates, analysts who are working on the grassroots level in conflict to build peace, are left behind to sit at the peace negotiable tables. This structural exclusion of women in the peace process further obstructs women to enjoy the UNSCR 1325.

Pressure To Speak In a United Voice

Women’s inclusion at the peace negotiation tables faces additional pressure, which is not expected from men in the peace process. To qualify for peace tables and have their recommendations valued, women are expected to form a collective coalition that speaks in a united voice. This criterion weakens women’s individuality and promotes the notion of group action as the sole way to be heard. It is critical to recognize that women who do not have access to a coalition should be respected equally to those who do.

Not Losing Our Hope and Faith In UNSCR 1325

Now, as we approach the 22nd anniversary of Resolution 1325, it’s time to consider where we proceed from here? – How to ensure that UNSCR 1325 is effectively implemented and becomes an actual success?

Apart from the women voicing their inclusion in the peace efforts, it is the moral duty of the national and international civil societies to ensure that the UNSCR 1325 becomes a living reality. Creating meaningful opportunities and spaces for women to engage in peacebuilding and exerting pressure on the government to increase female representation in decision-making posts, are key steps to ensure a more conclusive space for women in peacebuilding efforts.

In a world where gender equality is still a far-fetched dream and polarized gender thinking is a common phenomenon, we need to seize the opportunity to strengthen the vision of UNSCR 1325. It’s time to rebuild our efforts to harness the full potential of women in the peace process.

IVolunteer International is a 501(c)3 tech-nonprofit registered in the United States with operations worldwide. Using a location-based mobile application, we mobilize volunteers to take action in their local communities. Our vision is to create 7-billion volunteers. We are an internationally recognized nonprofit organization and is also a Civil Society Associated with the United Nations Department of Global Communications. Visit our profiles on Guidestar, Greatnonprofits, and FastForward.