Offshore finance structuring will continue to threaten the public good, nation development, and the world order – unless our leaders in power get serious about curbing its free and devastating reign.

For those of you looking blankly at the screen after reading the words ‘Pandora Papers’, you might want to check out this quick BBC explainer before you read on.

Now that we’re all up to date, did the revelations laid out in the ‘exposé’ shock and anger you?

Unfortunately, I barely raised an eyebrow. I’ll tell you why.

Earlier this year I started reading a book – ‘You cannot understand power, wealth and poverty without knowing about Moneyland’, declared a review on its cover. ‘Every politician and moneyman on the planet should read it’, advocated another. These gripping statements drew me in, hooked by a deep intrigue for this new word – ‘Moneyland’. The book, Moneyland: Why Thieves & Crooks Now Rule the World & How to Take it Back, written by investigative journalist Oliver Bullough, aligned with my pre-existing interest in the inequality and wealth gap discourse and seemed an essential and urgent read.

However, I wasn’t prepared for the huge blow to my perspective and worldview it was about to inflict.

Moneyland: a review of elite financial fraud

I cannot recall another book that has elicited in me the same level of horror and bewilderment as this one. For someone with little background in business and economics – and only a surface awareness of the workings of global finance – my eyes were well and truly opened to its sinister and self-serving aspects. With each page I turned in this meticulously researched and zealously investigated text, I was confronted with increasingly unsettling pieces of information. Slowly and methodically, it built up a comprehensive account of how ruling elites, criminals, and the super-rich exploit loopholes in the world’s financial system to move, hide, and grow outrageous amounts of wealth. It describes how governments are generally complicit, under-resourced or overwhelmed, and illuminates the private sectors housing the expert enablers who facilitate the whole operation.

Not only that, but this is far from a new phenomenon. The origins of the modern ‘offshore’ system – that continues to provide secrecy and impunity to anyone from a tax evader to a cartel boss – can be traced all the way back to the 1960s, with the creation of the Eurobond: a financial investment instrument that allowed its owners to move wealth covertly across jurisdictions, all whilst dodging taxes and paying a good rate of interest.

Throughout the book, I kept asking myself in disbelief, “how did I not know this is happening?” It may be the same question you asked yourself after looking into the Pandora Papers. This question does not have an easy answer.

Andy Beckett’s book review in the Guardian is blunt: “if you still have any illusions about the wonders of liberated capitalism, Moneyland will probably cure you.”

Moneyland is the matter-of-fact term Bullough uses to describe the shadow realm of globalized finance, where money and assets with anonymous owners flow freely – liberated from the imposition of transparency and accountability. It is his label for the common descriptor for this type of arrangement, offshore. Precisely, because the word offshore doesn’t go far enough to capture what’s really going on. What we are talking about is not something confined to a few small far-away islands – it permeates the very fabric of the world economy and monetary activity.

The wealth-hiding system, an ecosystem if you will, operates because of the tolerance and enablement of many different institutions and actors. It is not a minor sideshow in the larger economic system — it is the show. It is the system.

Chuck Collins, The Wealth Hoarders: How Billionaires Pay Millions to Hide Trillions

If you are familiar with offshore finance, and the way the rich and deceitful dance (for the most part) untouched, this will be business as usual – just as the Pandora Papers exposé did nothing more for me than prompt an audible sigh. However, if you are a fresh-faced newcomer about to enter this dark zone for the first time, I do warn you that it is an ugly place, one that you cannot readily unsee. A place that is hidden so cruelly in plain sight for anyone who takes the time to look for it, yet so frustratingly unstoppable. Even the most optimistic among us may falter in their step.

I refer frequently to Bullough, because his insights are gold if you want to get a grasp on the inner workings of this highly intricate and perplexing swindle. If this page sets you on a quest for more, I cannot recommend his writings, talks, and interviews on this topic enough.

Before I go on about why offshore is an issue that should trouble us all, let’s inspect more closely how it actually works, and the data leaks providing us with a significant look in.

The Pandora Papers

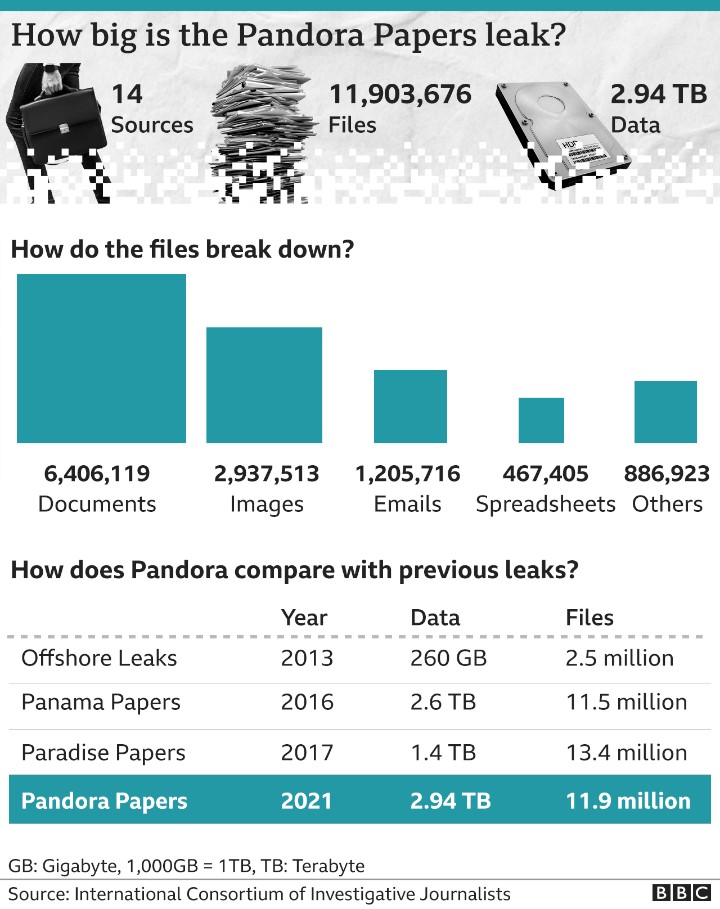

Earlier this month, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) (comprised of 280 investigative reporters from more than 100 countries and territories) revealed it received almost 12 million leaked documents exposing the offshore dealings of high-profile figures. The exposed individuals included celebrities, politicians, and world leaders – from pop-star Shakira to the King of Jordan. The ICIJ review also demonstrated how pervasive and widespread hidden capital and its vehicles of secrecy are. “The Pandora Papers show that the offshore money machine operates in every corner of the planet, including the world’s largest democracies,” wrote the ICIJ on 3 October.

Previous leaks

However, the Pandora’s box of offshore finance and secret wealth stashes was not opened this year. It has been opened countless times before. Media reports have tended to laud the most recent leak as a grand triumph based on its comparative size to previous ones. But excitement over the ‘biggest leak in history’ misses the point. Information is of course crucial to identifying the problem – but publications identifying the problem have been a recurring trend.

It doesn’t take much brainpower to connect past revelations with the latest Pandora Papers to conclude that despite all the fanfare, nothing much has changed. All these new documents do is just implicate more individuals in an already discovered system. We may be shown the new tricks of the trade, but if anything, it does more to highlight how unsuccessful our attempts have been at interrupting it in the first place. And how poorly leading democracies are doing at walking the walk.

A post by Professor Paul Wragg on The International Forum for Responsible Media Blog fiercely attacks the exposés on the ground that the procurement and public dissemination of mass amounts of private information is entirely unethical, criminal, and has no ‘public interest’ leg to stand on. He is scathing in his assessment of the media reporting on what he says, “has concerned perfectly legal transactions – offshore companies used as part of lawful financial arrangements.” Wragg adds: “Rich people have money and seek to avoid tax. This is hardly news.”

Wragg offers a valid point. There is no crime for simply possessing and storing money if it is yours, and nothing inherently wrong with deciding to spend copious amounts on personal luxuries, even if it looks obscene to an ordinary person. Dan Neidle, tax partner at law firm Clifford Chance, told the Financial Review that what some might consider a loophole that the rich capitalize on, is actually just a technical point of policy on certain transactions. Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair and his wife acquired a £6.5 million office building by purchasing the property’s holding company – a commercial strategy, conscious or not, that saved them from a £312,000 stamp duty bill. Under UK law, stamp duty is payable for the sale of real estate itself, not on the sale of a company that owns the real estate. “It’s a policy choice,” Neidle said. “If governments want to change that, they should.”

I’ll dig a little deeper into this legally permissible commercial web.

Offshore finance and tax havens are legal

‘Tax havens’, or jurisdictions with favorable tax and confidentiality laws, are legal. Sovereign governments are free to regulate companies and financial institutions within their borders with business and tax rules in whatever way they see fit, so long as it does not impinge on the terms of any agreements or international conventions they are bound to observe.

It is also worth noting there may be valid reasons to maintain a level of secrecy around your financial affairs. Privacy may be a matter of safety for some high-profile individuals.

So, whilst you might be thinking it’s grossly unfair that those named in the Pandora Papers can afford to shuffle their affairs between jurisdictions (playing the “game of jurisdictional Twister” as Bullough calls it), maximizing their wealth by curtailing tax obligations, it does not matter substantively. As long as the money is obtained legally, and offshore assets and profits are declared, these individuals have done absolutely nothing wrong in the eyes of the law. Only some of the newly uncovered activity in the Pandora Papers may be categorized as illicit.

The problem lies with the privacy and protection that these places afford. Individuals can hide wealth from their home countries using a complex front of structured ownership secrecy, benefitting from legislation that allows them to be discrete about it. When your ownership of assets and accounts is private, you can conceal them from the authorities without the need to declare them as your own. It is at this point of nondisclosure where the line is crossed – from tax minimization to tax evasion or fraud. And you can still get away with it.

It’s also not just rich individuals. Mainstream corporations such as Apple and Facebook make sure they have a seat at the table in the offshore ecosystem too.

Why would you let people and corporations stash their wealth on your shores? What’s in it for these tax-lax jurisdictions? In short, it all comes back to money. Hosting shell companies and trusts is a lucrative business for the financial sector, because people are willing to pay big for secrecy. On the surface, this is an attractive foreign investment stacked model that can offer quick and bountiful economic stimulation for struggling smaller nations or jurisdictions. But “such countries gradually become organized around the interests of people who don’t even live there, to the detriment of those who do,” warns a report in The Atlantic.

The same opaque and deliberately confusing business structures, corporate instruments, and banking secrecy that is so attractive to the rich, also makes the task of investigating who owns what for compliance purposes incredibly laborious and time-consuming. Lazy and disinterested financial regulators exacerbate the problem. This wickedly intricate design is one where people operate largely unaccountable and untraceable.

Merciless and profit-driven lawyers, accountants, bankers, real estate agents, and consultants, primarily from the West, are the professional enablers of this sly scheme. “Corruption is a force multiplier for the West’s enemies, and yet the West continues to accept dirty money into its economies by the billion,” states Bullough in Moneyland.

The company formation industry, a facilitator, has come under fire on many occasions – most famously in the case of 29 Harley Street. At the same time, the vast majority of companies created by company formation agents most likely have no link to fraud or impropriety at all. “The fact that First World tax avoiders and Third World kleptocrats both inhabit Moneyland is central to why it is so hard to do anything about it,” resolves Bullough.

It’s legal, who cares?

Before you believe me unreasonable or narrow-minded, I again want to acknowledge that many of these individuals’ fortunes are entirely legitimate, sourced probably from a generous inheritance or a grand salary like that of a movie star or business tycoon. You might argue that these individuals have a right to their genuine wealth, and a right to move it about the global financial web however they like, so long as they follow the laws of the jurisdictions they operate in. After all, it is the system that is enabling this beneficial asset protection. They may be creating a demand for schemes of secrecy, corporate veils, and tax havens, but why punish those with the smarts to make it work for them?

If this is what you see, if this is the message you take away from the leaks and the offshore world, then I am afraid you are not seeing the big picture. You do not fully appreciate the real consequences of allowing things to continue as they are.

Examining the wild figures of hoarded wealth, it’s hard not to feel overwhelmed. It begs the question, what on earth could anyone possibly need that much money for? How many luxuries can any one person buy? Just how much money does one need to accumulate and sit on? Maybe I ask these questions with an element of naivety regarding a person’s charitable convictions. Even so, I will say that I do not expect everyone else to share my same sincere care for humanity and wish to alleviate the suffering of those less fortunate.

But I do have a problem with the carelessness with which the system and its enablers allow corruption and criminal profiteering to occur.

Whilst offshore entities themselves may be legal, it does not necessarily mean they are not used as a vessel to participate in illegal activities or harbor unlawfully obtained money.

Unfortunately, the system that wealthy individuals and businesses use to employ what they call smart financial planning strategies to legitimately minimize tax obligations within its lawful – albeit sneaky – parameters, is also hijacked by others with more nefarious and very much illegal objectives of tax evasion and money laundering. The distinction between visible fiscal structuring and secret, dirty cash is lost in a world that caters for both. This is the problem at the very heart of hidden offshore opportunities, “which is that the same things that attract the naughty money – privacy, security, deniability – also attract the evil money,” explains Bullough.

Let’s consider for a moment that more and more people and businesses start playing this elaborate game of hide-and-seek with their assets. Because if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em, right? You shouldn’t be complaining if you can do it too. In this scenario, soon those who are not a participant in the scheme make up the minority, and would be primarily poorer and less educated. What do you think would happen to the funds of governments around the world who could no longer tax the majority of their citizens? Who will pay for our infrastructure, hospitals, and schools? How do poorer nations develop and get a chance at catching up?

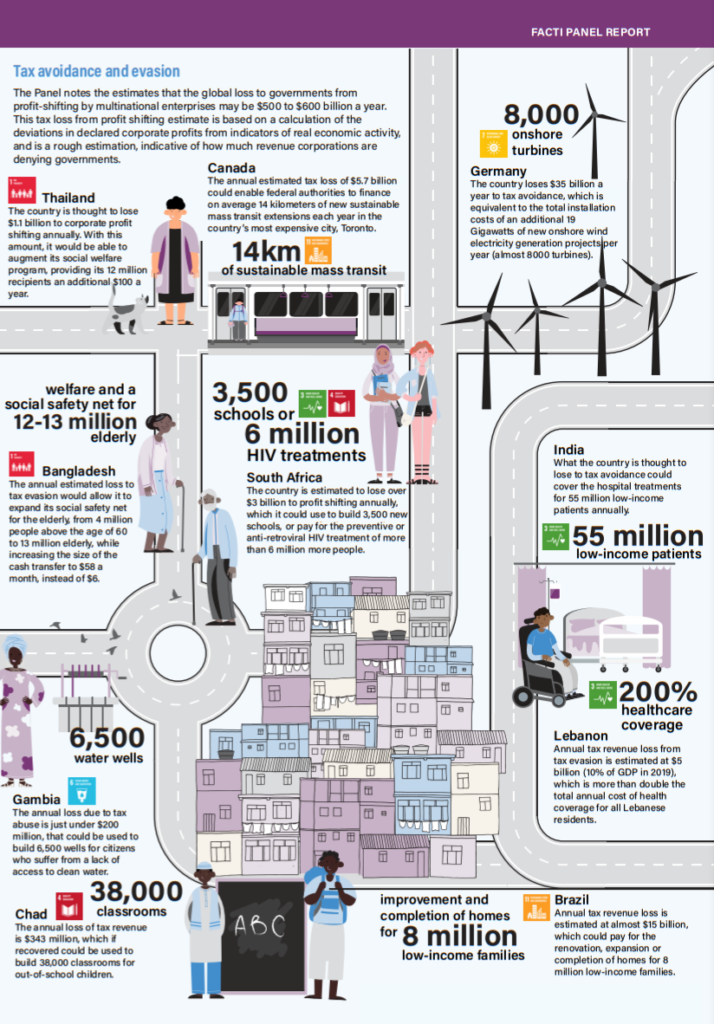

According to the 2021 report by the Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity Panel (FACTI), governments are already being denied large portions of revenue that could be used to benefit their people.

James A. Paul, a former Executive Director at Global Policy Forum, explained to Inter Press Service that the FACTI report is a “devastating analysis” detailing how the world’s financial architecture and rules make sustainable development (including the SDGs) problematic, bordering on impossible, to achieve.

“Companies can claim business expenses in high-taxing jurisdictions, and shift profits to low or no taxing jurisdictions, evading tax obligations and robbing countries of much-needed tax income for the provision of essential services,” Transparency International Australia’s Serena Lillywhite told ABC. And Emma Agyemang wrote in the Financial Review: “What the Pandora revelations highlight are inequalities within a tax system that gives the wealthy access to privileges not available to most.”

Someone with immense wealth doesn’t deserve to avoid paying for the benefits of a society they live in and use of its facilities just by virtue of said wealth, in the same way that anyone else does not deserve to do so. Bullough elaborated on this problem on Fresh Air for NPR: “The core function of a democratic government is to tax its citizens for the common good of everyone. Essentially, with the consent of the governed, it taxes its citizens, and then it uses that money for everyone’s good.” He continued, “If a class of society is able to opt-out of that contract, if they will essentially enjoy the privileges of citizenship without any of the obligations of citizenship, then they are opting out of democracy.”

Author and journalist Nicholas Shaxson shares Bullough’s concerns about the wider threat offshore poses to the public order. “But tax is only part of the story,” wrote Shaxson for The New York Times. “The global game of deceit, played for decades by the wealthy and their functionaries in the City [of London], has eroded the rule of law – and stripped away citizens’ trust in the system.”

This is not just about wanting the wealthy to pay their fair share of taxes to contribute to the world they live in. As important as preserving democratic values is, it’s just as important to take the wind out of the sails of global criminal syndicates, international terrorists, and corrupt dictators who continue to threaten international and national security and justice, causing ordinary people to suffer.

Tax dodging aside, what about the freedom of foreign direct investment and easy capital flow? That’s a good thing though, right? It stimulates the economy, the labor market, and development in countries that need it. An International Monetary Fund study in 2017 shows this is often not the case. It found that almost 40% of all foreign direct investment positions globally don’t actually find a way into the local economy: the investment simply passes through empty shell companies with no real activity.

You don’t need to be an economist to see that rich people’s ability to take advantage of offshore tricks is unavailable to the rest of us and is also part of the explanation for why our societies have become so much less equal. If the wealthy can dodge taxes, and even steal, with impunity, it will only expand the divide between those who own assets and those who don’t.

Oliver Bullough, Moneyland

Attempts to stem the bleeding

From time to time, we might hear our politicians talk about clamping down on tax avoidance and money laundering – using an array of dull catchphrases such as ‘anti-corruption crackdown’ and ‘transparency and tax reforms’. This does little to grab the interest of most people and references a vast world that can elude the comprehension of even those who work in it. Mostly, we go about our lives not caring to understand what they are talking about. Even worse, it barely scratches the surface of the dizzying extent to which the rich and powerful bend the rules to make them and their assets untouchable, nor does it appreciate just how immense the scale of action and international cooperation required to effectively combat it.

Still, there have been some moves in the right direction.

The OECD launched the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) in 2014. Countries who sign up to the CRS agree to automatically swap information to assist authorities to track offshore assets, enabling cross-checking of this data with the tax returns of their taxpayers to spot mismatches and identify the rule-breakers.

But perhaps you have enough money to buy citizenship by investment from a clever residency-for-sale business such as Henley & Partners, so that you can step around its reach and claim residence in a tax haven anyway. Or maybe you decide to stash your assets in the US, a country that is not part of the CRS (a disastrous loophole that undermines the regime’s aspirations). Under the US’s own foreign tax compliance legislation, more than 100 nations share information on overseas assets held by US citizens, but this is only minimally reciprocated. The result: the world’s leading democracy has cultivated a major tax haven opportunity for non-residents in its own backyard.

As Bullough points out in Moneyland, offshore secret wealth is “not a geographical location, it is a system, which emerges wherever conditions allow it to”.

In 2016, then UK Prime Minister David Cameron hosted a world-first anti-corruption summit in London. In his closing remarks at its conclusion, Cameron was clear about what we needed to do: “And I say again, if we want to beat poverty, if we want to beat extremism and narrow the gap between the richest countries in the world and the poorest countries in the world, we have to tackle corruption.” The Global Declaration Against Corruption was the bold achievement born out of this meeting.

A year later, Transparency International (TI) released an analysis on the progress of countries towards the commitments in the Declaration, and found that despite promising development by some, many were already falling behind or stalling. It noted that “very little action has been taken by three financial powerhouses – the US, Switzerland, and Japan. Two-thirds of the commitments made by these three high-income countries remain inactive”. You can keep tabs on the Anti-Corruption Pledge Tracker here.

Change on an international scale is often slow, we know that. But it really is disheartening when you see a strange complacency and disinterest coming from nations who are vocal on corruption and hypocritically engage readily in criticism of other ‘traditional’ tax havens, without addressing their own gaping regulatory loopholes. In an interview with The Paypers, Bullough explained that corruption has not been contained by borders for decades, and “the traditional division of the world between poor-and-corrupt countries, and rich-and-honest countries, is false.”

The UK is as much to blame when a Ukrainian official spends stolen money on a house in Kensington, as Ukraine is; and all the other countries that the money passed through – Estonia, Denmark, Germany – on its way, have a share in the blame too.

Oliver Bullough, The Paypers interview 28 September 2021

The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) by TI is also misleading. It does a good job at tracking the countries where bribery and theft occurs, but misses a key part of the process: where the proceeds of illicit activities are spent. TI even itself admits that “countries that perform best on the CPI are often the very same that enable high levels of illicit private sector activity, money laundering, and foreign bribery.” It’s rather ironic the anti-corruption summit was in London, as the city has “become the location of choice for oligarchs and corporate crooks to sanitize their ill-gotten gains”. London is enticing because it is an entirely respectable and trusted city to do business. The perfect place to hide in plain sight.

A certain disregard

When the world became aware of the Danske Bank scandal in 2018, political feathers in Denmark and Estonia were harshly ruffled. Surprisingly though, in the UK it was as if nothing had happened, even though shell companies registered in the UK and the British Virgin Islands made up two of the three biggest groups of account holders where money was being laundered through the bank’s Estonian subsidiary. It barely made a ripple in the UK government.

Howard Wilkinson, a British banker and the original whistle-blower in the scandal, had already shared his concerns with his superiors back in 2013, years before the 2018 investigation by a law firm reported on the flagrant negligence and wrongdoings of the bank. When providing evidence to the European Parliament, Wilkinson said, “Just as important and just as culpable are the countries where there are shell companies implicated in the schemes.” He made it clear there was no love lost between him and his home nation: “The worst of all is the United Kingdom. I think one has to be slightly polite when one comes to an institution like this, but one doesn’t have to be polite about one’s own country. The role of the United Kingdom is an absolute disgrace.”

All efforts to move in [the right] direction are welcome, but the problem so far is that those efforts have all been partial, and do not address the root cause of Moneyland, which is that money is international while laws are not. As long as some jurisdictions allow things that other jurisdictions do not, Moneyland’s gatekeepers will always find a way of exploiting the mismatches, just as they have with the differences in the information exchange requirements between the United States and the rest of the world…Loopholes provide opportunities, always.”

Oliver Bullough, Moneyland

To help you visualize the barriers to change, imagine the world as a Whack-A-Mole game. Each jurisdiction is represented by a separate hole, and the moles symbolize the mixture of dirty and legitimate money of the world’s crooks and elites. The moles appear in a hole that offers a safe harbor, away from pesky regulators and the public eye. It affords the mole secrecy and protection – the mole is accountable to no one. Those trying to tighten controls and do a makeover of the financial system to champion transparency, fairness, and anti-corruption are swinging the mallet. Most of the time, the mole is cunning and evades the mallet. On occasion, the mallet makes contact, stemming the flow of bad money momentarily, or uncovering enough information to prosecute the criminals associated with it.

But this is overall trivial. There are countless other holes for the mole to reside in because the holes are not acting with one, coordinated approach. The problem is all but shifted somewhere else that will welcome the mole and create an environment favorable to its objectives. This is why, despite years of revelations that have unearthed just how this system operates – and even those with a connection to it – the world has not even gotten close to rebuilding the global financial architecture in a way that will prevent this kind of activity.

…Moneyland will continue to evolve, its protections will continue to strengthen, as its imaginative and well-motivated defenders think of new ways for its citizens to hide and multiply their money, in whatever jurisdiction is most welcoming to them, whether that’s Nevis, the United Kingdom, the United States or somewhere else entirely. And this is a very worrying thought for anyone attached to the idea of democracy and the rule of law.

Oliver Bullough, Moneyland

The solution requires a dedicated team effort

I know I have painted an extremely bleak picture, but all is not lost. Countries have shown some teeth in tightening regulations and implementing reforms in response to discoveries of shady transactions or illegality. An example is the OECD/G20 BEPS Project, that with new developments this year, has made significant progress towards improving the coherence of international tax rules.

In pure tax terms, the Pandora Papers haven’t lit up concerns of evasion and illegal behavior like previous leaks. From a positive outlook, this could indicate that media exposure, subsequent investigations, stronger links on international transparency, and data sharing standards, have been a deterrent.

Yet still, it is obvious that our regulations have not kept up with the pace of the global and digitalized interconnected economy.

If the world is to stop billions upon billions of dollars draining into Moneyland, and away from oversight, it needs to act as one.

Oliver Bullough, Moneyland

Just like the effective tackling of climate change, COVID-19, and most other pressing issues of our time, remedying tax evasion and corruption requires buy-in from everyone. And it needs powerful, resourced nations to assist the weakest links by investing in the stability and manpower of revenue departments in the poorer parts of the world. Because some of those countries just do not have the capacity to match. A United Nations write-up in the Inter Press Service stressed the importance of developed countries working to alleviate financial and capacity restraints that prevent less well-off countries from participating in global transparency and information exchange schemes.

This month, 136 nations signed up to a deal setting a minimum global corporate tax rate of 15%. However, already there have been questions about its feasibility and the next steps for implementation. The solution will also require more than uniform transparency and reporting benchmarks, smooth data-sharing, and teamwork between richer, well-resourced nations and poorer, less-stable economies. Although, these elements are indeed crucial. It is also vital that there is a trust relationship from taxpayer to government that state funds will be spent appropriately and for the good of society – not stolen by corrupt leaders or spent tactically as part of a political game. If the people must be transparent, so too must public officials and institutions be open to scrutiny and held accountable for the allocation of state revenue, to stop creating a reason for people wanting to hide their money from a government they cannot trust in the first place.

I do not envy those allocated with this problem-solving task. Tax regimes in one jurisdiction alone are difficult to master a working knowledge of. And the way that policy is created and revenue collected is typically tied to local forces and needs. Marrying up an entire world of regimes and the authorities that implement them does seem a diabolical challenge. Although, this should not be a reason for inaction.

It’s cliché, but true: where there’s a will, there’s a way. And everyone needs to be on the same page.

What you can do

Governments and international bodies have been dragging their feet, and despite recent progress towards a more harmonious global taxation approach, it is often journalists, researchers, NGOs, and other groups that have to keep reminding them of just how pressing this issue is.

Since 2003, the Tax Justice Network has advocated for the reprogramming of tax systems to work for all of us, not just the rich, and to repair the injustice and inequality that the current framework fuels. The Network researches tax policies and laws to measure their negative impacts and inform our governments and wider society. Most importantly, it is helping to devise a solution by developing alternative, equality-focused tax policies that governments can implement in order to better and more fairly wield the powerful tool of tax. You can support the Network through donations, working for them if an opportunity arises, or educating others in your own community through the many videos, reports, podcasts, and other material available from its website.

Supporting the organizations and people that have standing, are visible, and can apply pressure on governments to change the system is what we can do as individuals to help. And at the most basic level, we need to make this issue more known and more talked about in our own circles. If we are all aware of just how damaging the status quo is to overall global equality and prosperity, maybe we can get enough momentum and voice behind the movement.

IVolunteer International is a 501(c)3 tech-nonprofit registered in the United States with operations worldwide. Using a location-based mobile application, we mobilize volunteers to take action in their local communities. Our vision is creating 7-billion volunteers. We are an internationally recognized nonprofit organization and is also a Civil Society Associated with the United Nations Department of Global Communications. Visit our profiles on Guidestar, Greatnonprofits, and FastForward.