The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic saw the hasty manufacturing, distribution, and production of vaccines. To curb the spread of the virus and safeguard individuals from the pandemic, vaccines had been either procured or distributed based on the purchasing power of states. However, this distribution has not been a seamless process, with grotesque inequalities in vaccine distribution based on a countries’ status. Fundamentally, the World Health Organization has criticized what it has termed a “shocking imbalance” in the distribution of vaccines between high-income and low-and-middle-income nations (LMICs).

On average in high-income countries, almost one in four people have received a Covid-19 vaccine. In low-income countries, it’s one in more than 500.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director General, 2021

The Inequality in vaccine distribution

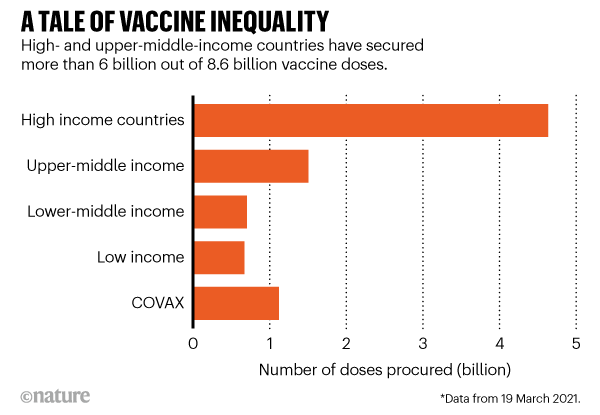

Data from the Duke Global Health Innovation Centre Launch and Scale Speedometer – which monitors the procurement of COVID-19 vaccines – has found that high-income countries currently own more than 56% of all the global doses of vaccines purchased. It further makes the estimation that there will not be enough vaccine doses to inoculate the world’s population until at least the end of 2023. Research further makes evident that from the remaining 46%, 33% have been purchased by LMICs, who account for a staggering 81% of the global adult population. This is contrasted with research that stipulates high-income countries currently have enough vaccine doses to cover more than twice of their adult population.

This alarming situation has been progressively worsened by high-income countries cutting direct deals with vaccine producers. This has resulted in high-income countries procuring a disproportionate share of early doses. Disregarding the joint efforts of the United Nations and the World Health Organization in the plea to ration purchasing, the actions of these countries has resulted in a crisis that cannot be easily remedied.

Implementation of policy schemes to mitigate the divide

The current ‘me first’ approach will ultimately cost more, in terms of lives

Diane Abad-Vergara, COVAX communication focal point, 2021

The primary global vaccination scheme that is currently operative is the COVAX Facility. Funded by the UN, it is the only international initiative in place to ensure that the COVID-19 vaccines are available to all countries regardless of their ability to purchase or their income levels. The central objective of the COVAX scheme is the facilitation of 2 billion vaccine doses to a quarter of the population of all underdeveloped countries in 2021.

The operation of the COVAX scheme has been largely fruitful with over 100 economies being granted 38 million doses of vaccines. This figure however pales in comparison to the overall target of 2 billion. Additionally, there are numerous issues concerning the continued operation of the program – primarily export controls, lack of funding, and vaccine hesitancy.

Export Controls

People’s health first’ has been the guiding principle, driving all efforts in the fight against the pandemic – both nationally and globally – to ensure that “No one is left behind”

H.E Dr. Tawfig AlRabiah, Minister of Health in Saudi Arabia, 2021

While the COVAX scheme may seem feasible on paper, there are a multitude of issues concerning the implementation of the program. A key concern is the enabling of export controls by manufacturing states that hamper the rollout of vaccines to the needy. Export controls – inclusive of commodity controls, prohibited destinations, and denied party lists – actively hinder the global supply chain that facilitates the distribution of vaccines from one point to the other.

The financial resources that are utilized in producing the vaccine are squandered due to the restrictions imposed on distribution. This is because the rollout of vaccines to LMIC states is the need of the hour and has to be immediate. Therefore, a delay in distribution of the vaccines results in an increased death rate making the initial investment in the vaccines itself, a waste of funds.

This is exacerbated by the notion that the UN and the COVAX body do not have the jurisdiction to regulate export controls. First regulated by the European Commission of the European Union, the imposition of export controls is entirely in the command of member states themselves. Additionally, export controls serve the interests of the European Union and the manufacturing states from an economic perspective. Accordingly, the imposition of export controls enables these parties to favor the exports of one producer over another for economic gain. This is notwithstanding the notion that this calculus takes little account of the risks to European public health should foreign governments take stringent measures in response to the export control regime on COVID-19 vaccines.

It is apparent that developing and underdeveloped states have been altogether excluded from the equation as beneficiaries, with member states unwilling to compromise on the potential economic gain through the vaccination program itself. Therefore, COVAX is seemingly up against a strong force that remains profit-oriented, even in the face of a global pandemic.

Lack of Funding

Funding is a perennial concern, even in pandemic response

Diane Abad-Vergara, COVAX communication focal point, 2021

While several high-income nations and organizations – inclusive of the United Kingdom, the United States of America, China, and the European Union – have contributed much to closing the vaccine funding gap, this has evidently not been enough. While funding to produce vaccines has been effectively lobbied among states, funding for the delivery of those vaccines has become increasingly problematic. This is attributed to inconsistencies in export controls and supply chains.

To continue providing vaccines to its 190 members, COVAX needs at least $3.2 billion in 2021. The faster that this funding target is achieved, the faster that vaccines can get into people’s arms

Diane Abad-Vergara, COVAX communication focal point, 2021

A staggering amount of $2 billion is required to assist the 92 states at the bottom of the LMIC spectrum – which constitute the poorest countries in the world. UNICEF estimates that $510 million of this amount is urgent and is required to procure essentials such as vaccinators, health worker training, refrigerators, and delivery trucks. It is apparent that funding is the primary factor contributing to vaccine inequality, and is exacerbated by the notion that even the richest countries have a tight hold on their treasury in the present day.

Vaccine hesitancy

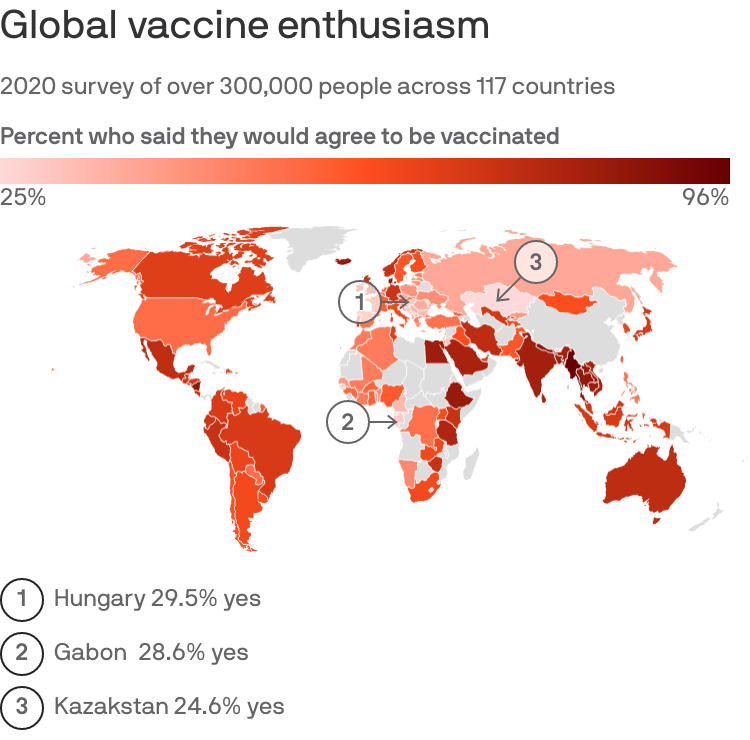

Defined by the World Health Organization as a “delay in acceptance or refusal of safe vaccines despite availability of vaccine services”, vaccine hesitancy is a primary factor contributing to the inequalities in vaccine distribution. Vaccine hesitancy is caused by complex and context-specific factors that are influenced by issues such as complacency, convenience, confidence, and sociodemographic contexts. Primarily related to misinformation spread online – especially through social media – vaccine hesitancy is primarily attributed to socioeconomic disadvantages, systematic racism, and barriers to access.

Research suggests that only 68% of adults globally have agreed to get vaccinated provided that the shot was available to them at no cost. This is less than the estimated 90% that is required for the world to reach herd immunity, and effectively be ‘COVID-19 immune’. Accordingly, vaccine hesitancy – while not a primary factor in reducing inequalities – may be the prime factor between an inoculated community, and one that remains susceptible to COVID-19.

An urgent call for help

Several measures to counter the inequality in vaccine distribution have been taken. The People’s Vaccine Alliance – a coalition of organizations such as Oxfam, UNAIDS, and Global Justice Now – accused vaccine producers of ‘strangling’ the global supply of vaccinations through their intellectual property protections. This allegation was furthered with a proposition by member states to halter the operation of the Technical Agreement governing Aspects of Intellectual Property, which secures these protections. However, it is inevitable that these attempts have fallen victim to political play within larger organizations.

Youth organizations inclusive of ActionAid International, Youth Lead Africa and Rotaract International have taken the forefront in advocating for vaccine equity. Additionally, climate, environment, and youth advocate, Greta Thunberg has joined the struggle for vaccine equity. These organizations and individuals have been imperative in urging countries and manufacturers to boost and share COVID-19 vaccine supplies to ensure equitable vaccination.

The inequality in vaccine distribution should not be undermined in the hope that the issue recedes. It is one that will only worsen in time and requires immediate attention. Accordingly, youth engagement and advocacy concerning this pertinent issue is mandatory, and remains one of the only viable measures that may be taken. Youth workers are strongly encouraged to work in conjunction with Aid Organizations in advocating for the equality of vaccine distribution.

IVolunteer International is a 501(c)3 tech-nonprofit registered in the United States with operations worldwide. Using a location-based mobile application, we mobilize volunteers to take action in their local communities. Our vision is creating 7-billion volunteers. We are an internationally recognized nonprofit organization and is also a Civil Society Associated with the United Nations Department of Global Communications. Visit our profiles on Guidestar, Greatnonprofits, and FastForward.