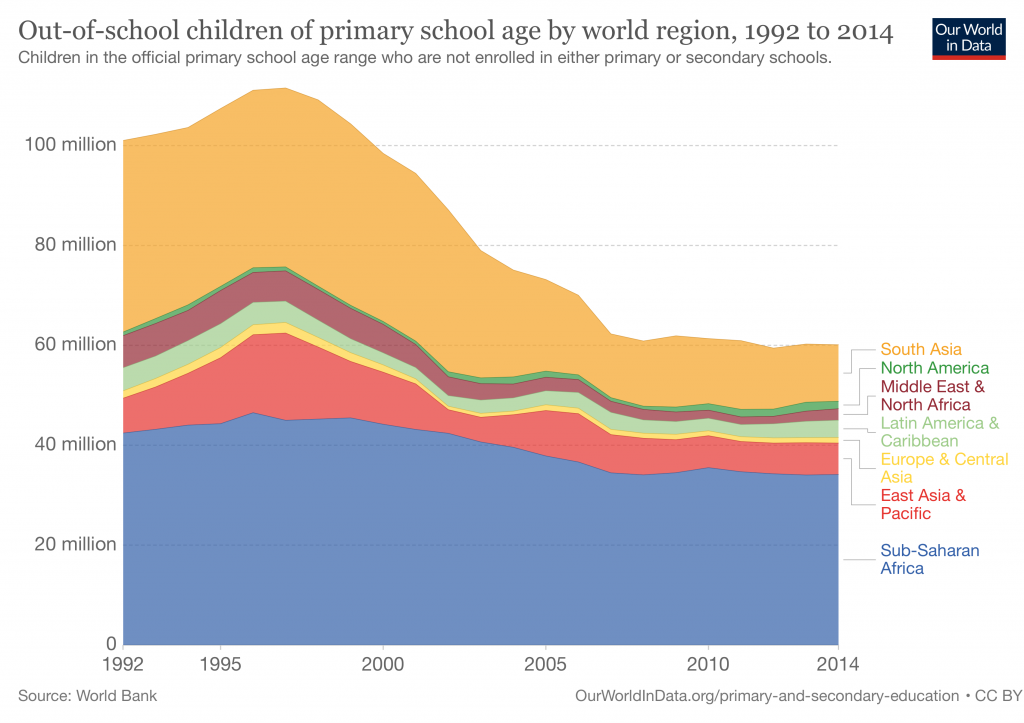

For many years, access to education has been rather unequal. Especially in developing countries with high inequality indexes, even a good primary education is treated as a privilege. There are an enormous amount of factors that determine both the access and the permanence in schools. Whether it is an economic issue, a gender issue, or a geographical one, obtaining this basic service is differentiated around the world. Arguably, it could be said that the type of household you were born in determines the amount and quality of education that you will receive throughout your entire life. According to Roser & Ortiz-Ospina, there were 60 million children of primary school age who were out-of-school in 2014, with the majority of them in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Although universal coverage in education has been addressed by governments, that is not the complete issue. Different policies have been effective when it comes to getting children to school, but that is not by any means enough. Actually, universal coverage is far from sufficient when it comes to the quality of the education given. There is no value going to school if you have not been taught what is really necessary. Furthermore, the backgrounds of the students matter even more. It is not just an issue of getting classes, but of quality, care, nutrition and entertainment (Castillo, 2014). Therefore, multidimensional poverty makes itself very much important when it comes to guaranteeing the fundamental right of education.

According to ACNUR (2018), malnutrition and school performance have a strong link. The first can cause a reduction in attention, lack of concentration, a delay in physical and cognitive growth, among others. In this sense, children from a middle-high class already have a kickstart when it comes to their learning. Moreover, the quality of the education per se, the disponibility and facility to attend classes daily as well as the commodities of the infrastructures are other key points to keep in mind when studying differentiated education.

The New Scenario

Since the outbreak of the current crisis driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, this situation has been worsened. Pursuant to the recommendations issued by the World Health Organization, most of the countries found it necessary to implement extreme measures such as lock-downs to slow down the spread of the Coronavirus. Consequently, most schools around the world ended up being closed, thus exacerbating the existing inequality when it comes to learning. Anderson (2008) studied the challenges of e-learning in developing countries and found seven major obstacles to face: student support, flexibility, teaching and learning activities, access, academic confidence, localization and attitudes. Moreover, Aung et al. (2016) found challenges such as poor network infrastructure, lack of ICT knowledge, weakness of content development, among others. Bear in mind that these analyses were made prior to the pandemic. In light of the uncertainty that the pandemic has created globally, one can just imagine how these constraints have become worse.

As a result of the abrupt implementation of e-learning throughout the world, millions of children were affected in a negative way. Engzell et al. (2020) studied the real impact of school shutdowns during the pandemic in the Netherlands, and noted the devastating results. Their research revealed:

The average learning loss is equivalent to a fifth of a school year, nearly exactly the same period that schools remained closed. These results imply that students made little or no progress whilst learning from home, and suggest much larger losses in countries less prepared for remote learning.”

(Engzell et al., 2020)

Moreover, they found that losses are up to 55% larger in students from less-educated households, which clearly demonstrates how remote learning has widened the gap in education inequality. It is important to note that the Netherlands is a good case study because of its high degree of technology preparedness and relatively short lockdown of eight weeks. Further afield in Latin America, the effects of the pandemic on education have been quite worrying.

As uncertainty rules during these times, many Latinamerican governments implemented extreme policies as the first case of infection was detected. This caused an extensive period of quarantine in which schools were closed. For instance, in August, more than 140 million students stayed five months without attending school in Latin America and the Caribbean (García, 2020). Therefore, and following Engzell’s results for the Netherlands, the deficit in learning for these millions of students could be greater than half a school year lost, or even worse in students from less-educated families.

Further Action

In her analysis of the current situation, García (2020) lays out a series of recommendations that need to be implemented in order to counteract these effects:

1) plan the reopening of schools with a sense of urgency;

2) develop a strategy that ensures the learning of all students in the midst of the new context where not all hours of instruction will be in person;

3) maintain the protective role of school and guarantee services that have been interrupted; and

4) ensure the emotional well-being of the educational community (teachers, families and students).

(García, 2020)

Moreover, this could be an opportunity to design an educational system that not only neutralizes the effects of the pandemic, but also closes the gap in educational inequality. For this to happen, García notes that governments must have a long-term vision when designing what is to be done. This way, they could design a whole new system that remains even when the pandemic is over, that is sustainable and that protects the fundamental right for education.

Furthermore, there must be a spread of awareness about what is going on with schools. As this is an uncertain time and many people are extremely scared to go out, many parents would not allow their children to attend school even if they were open. Therefore, they do not know about the consequences that will have on their kids´ education and how ir will affect their entire life. Hence, it is not only important to open schools, but to spread the evidence that has been found so that every household can decide objectively about what to do with their children.

References

ACNUR. (2018). Influencia de la nutrición infantil en el rendimiento escolar. Available at: https://eacnur.org/blog/influencia-de-la-nutricion-infantil-en-el-rendimiento-escolar-tc_alt45664n_o_pstn_o_pst/

Andersson, A. (2008). Seven major challenges for e-learning in developing countries: Case study eBIT, Sri Lanka.

Aung, T. & Khaing, S. (2016). Challenges of Implementing e-Learning in Developing Countries: A Review. 388. 405-411. 10.1007/978-3-319-23207-2_41. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284898156_Challenges_of_Implementing_e-Learning_in_Developing_Countries_A_Review

Castillo, M. (2014). Determinantes de acceso a la Educación Inicial. Available at: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Colombia/alianza-cinde-umz/20150306114229/MaribelCastilloCaicedo.pdf

Engzell, P., Frey, A., & Verhagen, M. D. (2020). Learning Inequality During the Covid-19 Pandemic. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/ve4z7

García, S. (2020). COVID-19 y educación primaria y secundaria: repercusiones de la crisis e implicaciones de política pública para América Latina y el Caribe. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/covid-19-y-educaci-n-primaria-y-secundaria-repercusiones-de-la-crisis-e-implicaciones

Roser, M & Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2013). Primary and Secondary Education. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/primary-and-secondary-education#citation

IVolunteer International is a 501(c)3 tech-nonprofit registered in the United States with operations worldwide. Using a location-based mobile application, we mobilize volunteers to take action in their local communities. Our vision is creating 7-billion volunteers. We are an internationally recognized nonprofit organization and is also a Civil Society Associated with the United Nations Department of Global Communications. Visit our profiles on Guidestar, Greatnonprofits, and FastForward.