A moratorium on the death penalty actively captures 21st Century ideals – with international conventions and organizations actively campaigning for the abolition of capital punishment. However, the legalization of the death penalty in 14 countries, with 18 countries carrying out executions in the year 2021, demonstrates that member states are far from accepting of the trend for abolition. While crime remains rampant globally, is it only worse in developing and least-developed countries, and this remains true for Sri Lanka. This has pushed the state to consider capital punishment by lifting the moratorium on the death penalty. However, this lifting is not only a violation of fundamental rights, but may also not be as deterring as the Sri Lankan state would hope.

The route to capital punishment in Sri Lanka

After gaining independence in 1948, Prime Minister S.W.R.D Bandaranayake abolished capital punishment in 1956. However, it was reintroduced upon his assassination in 1959. This reintroduction was amended in 1978 and death sentences could only be passed if authorized by the trial judge, the Attorney General and the Minister of Justice, unanimously. Upon disagreement, the sentence would effectively be commuted to life imprisonment. The last known execution by the state was the execution of that of ‘Maru Sira.’ Owing to his daring escapades from his prison cell, the guards drugged him a day prior to his trial resulting in him being unable to stand for the noose to be placed correctly around his neck. This resulted in a botched execution ceasing capital punishment in 1976.

Following the swearing in of President Chandrika Kumaratunga, there was effective campaigning to re-introduce the death penalty. However, this could not be done owing to immense public backlash. Circumstance arose nevertheless upon the assassination of High Court Judge Sarath Ambepitiya in 2004 as he headed home from work. This prompted the immediate restatement of capital punishment. In a recent attempt to drastically reduce drug crimes and sex crimes in the nation, the government has pledged to restore the death penalty. On account that the moratorium is lifted, executions will take place for the first time in 42 years.

Sri Lanka’s international commitments and human rights obligations

The stance of International customary law on the death penalty has evolved over the centuries, favoring the abolition of the death penalty. Sri Lanka is party to several international conventions such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the first Optional Protocol to the ICCPR; Recognizing jurisdiction of the Human Rights Committee and has additionally, voted in favor to several United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Moratorium Resolutions in the years of 2008, 2010, 2014 and 2016.

The policy followed by the ICCPR on the death penalty

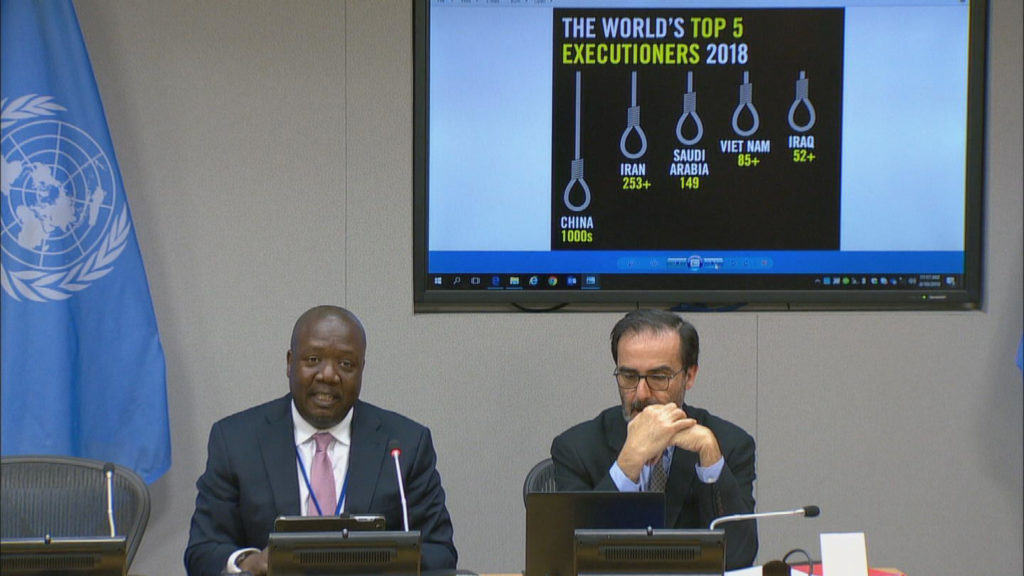

Some governments conceal executions and enforce an elaborate system of secrecy to hide who is on death row, and why

Antonio Guterres, Secretary-General of the UNO, 2017

Established as a multilateral treaty adopted by the UNGA, Article 6.1 of the ICCPR stipulates that states must ensure the right to life is inherently protected. At the forefront, human life is given prominence by the covenant, and states that are parties to the covenant are obliged to protect this fundamental right over that of the death penalty, which seeks to deny it. Nevertheless, provisions to derogate from Article 6.1 have been provided in Article 6.2 which allows states to implement the death penalty on the grounds that perpetrators have committed a ‘serious crime.’

The definition of a ‘serious crime’ is ambiguous, and cannot be narrowed down, owing to varying legislature across states. The most crucial interpretation stems from the statements of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions. In this statement, it was established that the death penalty should be abolished for crimes such as economic crimes, drug-related crimes, crimes opposing moral values such as adultery and prostitution, and victimless crimes. Nevertheless, the Islamic states impose the death penalty for crimes such as adultery, apostasy and witchcraft, alongside Singapore that regards drug offences as a serious crime. While these states may not mirror the interpretation of the Special Rapporteur, they encompass the exception to the majority.

The stance of the United Nations on the death penalty

The death penalty has no place in the 21st Century

Antonio Guterres, Secretary General of the UNO, 2017

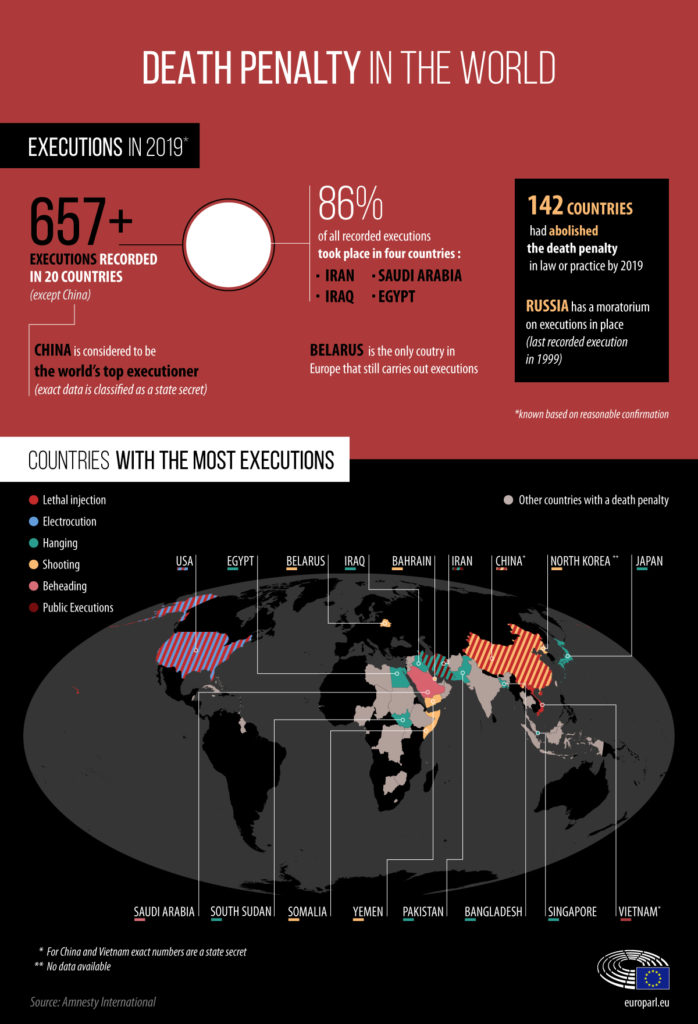

The UN is drastically inclined towards the abolition of capital punishment. Additionally, the UN upholds that countries that continue implementing capital punishment fail to meet international obligations in alliance with international human rights standards. Several commissions initiated by the UN have been established with the sole objective of eradicating the death penalty: the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) being the most significant. Among its efforts is the Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR – which effectively calls for the abolition of the death penalty. This is the only universal international instrument that calls for the official end of this practice. Interestingly so, Sri Lanka is neither a party, nor a signatory to this convention. The question of being legally binding would adhere to parties of signatories of the convention only, thereby effectively excluding the state from liability.

Moratorium on the death penalty: UN General Assembly resolution adopted in 2016

The resolution adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2016, with 117 states voting in favor of the resolution and 40 against, calls on states that have not abolished the death penalty to strongly consider abolition. Additionally, Section 7 (d) calls upon states to “progressively restrict the use of the death penalty and not to impose capital punishment for offenses committed by persons below 18 years of age, on pregnant women or on persons with mental or intellectual disabilities,” and further to “to reduce the number of offenses for which the death penalty may be imposed”.

While the Sri Lanka Penal Code of 1885 prohibits the use of the death penalty on individuals below the age of 18, pregnant women, the intellectually disabled, and the mentally ill, the Penal Code does not restrict the use of the death penalty overall. Alternatively, the state imposes the death penalty on 22 offences – inclusive of Robbery not resulting in death, Kidnapping not resulting in death and Drug Possession; crimes considered ‘not so serious’ by the Special Rapporteur on Extra judiciary, Summary or Arbitral Executions.

In an analysis of countries that have not abolished capital punishment, the crimes punishable by death are very limited. In the United Kingdom, these crimes encompass murder, high treason, piracy, and arson. Similarly, the United States of America imposes the death penalty for crimes of treason, murder, and genocide. Moreover, the Islamic countries’ imposition of the death penalty is based on Sharia law, and the list of crimes punishable by death totals 14 crimes; a number much lower than in Sri Lanka. Accordingly, it is argued that Sri Lanka is in non-compliance with Article 7(3) of the resolution which requires states to impose the death penalty on the most serious crimes. Additionally, lifting the moratorium on the death penalty may signify to organizations such as the United Nations a seemingly backward stance adopted by the state.

The reasoning behind the then President’s agenda in lifting the moratorium

The reasoning pertaining to the stance of the President in lifting the moratorium on the death penalty is two-fold. Firstly, the alarming increase of drug related crimes in the state, and secondly, the rapidly advancing rate of sex crimes and sex offenders.

The alarming increase of drug offences in the state

My order is shoot to kill you. I don’t care about human rights, you better believe me

Rodrigo Duterte, President of the Philippines, 2020

In 2018, the state made clear that drug dealers would be executed in order to “replicate the success” of the war on drugs in the Philippines. Arriving from a visit to the Philippines, the then President was so enamored with the apparent success of the state in minimizing crackdowns, that he was ready to ‘sign the warrants’ of repeat drug offenders. While this stance is rather extreme to an extent, the state may have justifiable grounds to be concerned – owing to the alarming increase of drug crimes and drug offenders during the years.

The drug epidemic in Sri Lanka has been a plague to the state since the year of 1980. This year in particular saw a growing cohort of opium and cannabis users, initially confined to Colombo and the South. In 1982, the Interpol confirmed Sri Lanka’s status as a transit country for the transportation of heroin in to Europe. Upon the confirmation of this status, rules and regulations were tightened to this regard, resulting in the amendment of the Poisons, Opium and Dangerous Drugs Ordinance of 1929. This resulted in the enactment of legislation enforcing the death sentence for drug related offences, and the creation of the National Dangerous Drug Control Board to regulate drug control in the state. Additionally, 45% of the total prison population constituted drug offenders in 2020 as per the National Dangerous Drug Control Board.

Despite these efforts, the sale and circulation of drugs in Sri Lanka have only escalated in number. In 2018, the Police Narcotics Bureau confirmed that 48,129 people had been arrested in connection to the possession of drugs, and more than 2,975 kilograms of Cannabis had been taken in to custody. Further, a cache of heroin worth over 1.2 billion rupees was seized during a raid conducted in Kalubowila; reportedly the largest stock of heroin ever seized by authorities. Additionally, the Police Narcotics Bureau nabbed 278 kilograms of heroin estimated at a staggering 3000 million rupees. This cements the growing concern that the state effectively functions as a regional drug distribution hub in the South Asian region. The question of whether the most effective method of curbing the drug issue in the state is the execution of drug offenders however, is yet to be established.

The heinous nature of sex crimes committed

Apart from drug offenses, sex crimes committed within the state are also of grave concern. The rape rate in Sri Lanka as of 2013 was 10.6 cases per 100,000 persons. This rate has progressively increased by 6.57 % annually. Accordingly, there has been a public outcry demanding capital punishment for the perpetrators of this crime. Two incidents, in particular, were the rape and murder of Seya Sadewmi, aged 4, and Sivalokananthan Vidya, aged 18.

In addressing the rape and murder of Seya Sadewmi, the accused was sentenced to death by the Negombo High Court. Of immense significance was the public outcry demanding the death penalty for the accused prior to the hearing. This was given bearing by Dr. Sudarshini Fernandopulle, when she called for the immediate implementation of the death penalty – citing the case of Seya as a ‘special case deserving of this’. Additionally, the brutal gang rape and murder of S. Vidya drew nationwide protests – owing to the circumstances leading to her murder. Raped by 9 men, the case concluded at the Jaffna High court with 7 of the accused been sentenced to death. Protests vehemently demanding the death penalty for all of Vidya’s rapists were conducted in the Ampara and Trincomalee Districts.

Additionally, the citizens of the North attacked the houses and suspects on the day of the hearing. These protests upon turning violent, required the police to use tear gas to disperse the protestors. It is clear than in these circumstances, the public clearly expressed their desire for punishment in the form of the death penalty. The notion that justice was taken in to their own hands expressed clear frustration that justice wasn’t meted out as fairly as the people expected.

The public demand for capital punishment

From now on, we will hang drug offenders without commuting their death sentences

Rajitha Senaratne, Spokesperson for the Sri Lankan President, 2019

Research conducted within the state established that ninety percent of the population approved of the President’s proposal to reactivate capital punishment in containing crime. International affairs student Sneha Devesundera was of the opinion that the death penalty would “stop rapists and drug dealers from operating.” Social scientist Dr. Nihal Jayatillake shared a similar perspective and he stated that he supported the reintroduction of hanging as it would “stop the crime rate.”

It is clear that the citizens of Sri Lanka strongly believe that the execution of rapists and drug offenders would create a crime- free society in the long run, but it must be remembered that this is merely perspective and opinion. It is essential that in validating these statements, an analysis on if capital punishment is an effective deterrent of crime needs to be carried out. The state has admittedly placed the needs of the people above that of international commitment. While this is a clear choice made by the Sri Lankan government, the violation of international conventions does carry consequences, and thereby an analysis on if there is an actual deterrent effect on crime with the establishment of capital punishment will follow.

Is the death penalty a deterrent for crime?

An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind

Mahatma Gandhi

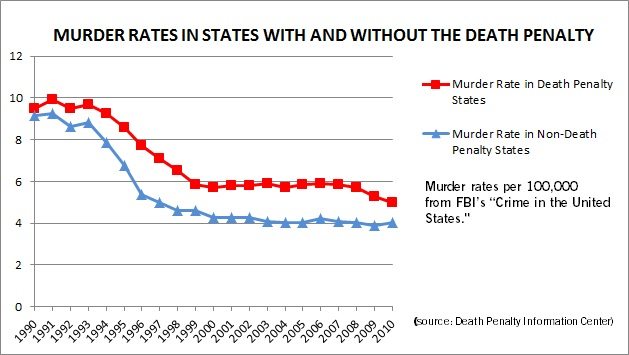

In lieu of the gamble the state takes in prioritizing the needs of the people above international commitments, the question of whether the death penalty has a deterrent effect on crime rates must be addressed. Research conducted by the Death Penalty Information Center in the USA taking in to consideration a total of 50 states does not support the existence of a deterrent effect. Statistics demonstrate that the rate of murder in states that have imposed the death penalty have remained higher in comparison to states that have not. Additionally, the National Research Council of the National Academics in the USA concluded that the death penalty had no deterrent effect on committing or preventing murder. Additionally, 88% of criminologists in the world do not believe that the death penalty deters crime.

In a second analysis, research conducted by the Harm Reduction International Group provided similar results. As per 2011, the number of drug traffickers’ on death row in Indonesia amounted to 157. This number increased to 202 in 2012 and 260 in 2013. These statistics make it evident that despite the implementation of the death penalty and the rigorous enactment of executions, drug trafficking has not been deterred in the least. Another alarming concern common to many Asian states is the ability of drug traffickers even whilst imprisoned to commission their operation within prison. Thereby, regardless of the notion that these perpetrators are on death row, the crime is still very actively continued, making any plausible deterrent effect seem null and void.

In a third analysis, research carried out by the Pew Research Center in affiliation with Columbia Law School compared the murder rate in Hong Kong upon the abolition of capital punishment and contrasted these findings with the murder rate in Singapore which establishes a mandatory death sentence for murder and drug crimes. Statistics from this research demonstrate that the murder rate in Singapore was 0.2% higher than that of Hong Kong. This only cements the ideal that there is no deterrent effect capital punishment plays in influencing the rate of crime.

Hanging by a thread

With no apparent deterrent effect on the rate of crime, the consequences of violating international commitments and failing to adhere to human rights obligations would be immensely disadvantageous to the state. Regardless of the public outcry, lifting the moratorium of the death penalty would by no means curb the rates of crime as established in this research. It is integral that alternative measures are pursued in aligning with modern standards, and the state would do well to look into other means of eradicating drug crimes and sex crimes.

IVolunteer International is a 501(c)3 tech-nonprofit registered in the United States with operations worldwide. Using a location-based mobile application, we mobilize volunteers to take action in their local communities. Our vision is creating 7-billion volunteers. We are an internationally recognized nonprofit organization and is also a Civil Society Associated with the United Nations Department of Global Communications. Visit our profiles on Guidestar, Greatnonprofits, and FastForward