No Order, No Peace

Horror vacui, a fear of emptiness can be likened to the coming age in international affairs. The era of western-led order is ending and we, as citizens of a globalised world, now coexist in a nonpolar international spectrum. Power has diffused and is no-longer held by monopolising states or alliances in the traditional sense. On this new stage, disorder is the norm and power is more about the ability to disrupt than to build. Since the 2008 financial crash, trust in market liberalisation has weakened, giving rise to protectionism and international institutional failure. International cooperation has suffered as the US led order has started to fade, leading to international dysfunction. Such a fact is manifested by the unravelling of treaties such as the Paris Climate Accord and the Iran Nuclear Deal (JCPOA). In this climate of demagogues and autocrats, it has become starkly clear how hard it is to produce a synergetic response to a global virus. Worse still however, the pandemic is accelerating this chaotic phenomenon, consolidating the power of nationalistic, isolationist and xenophobic groups both within the the liberal world and further afield (Fukuyama, 2020). As such, this revelation connotes danger, theorists are already predicting a so-called ‘new Cold War’ between the US and China, and based on the responses of the west and east respectively, it seems the latter may emerge in the post-pandemic world largely on top.

Photo Credit: Financial Times ‘China’s Belt & Road Initiative’

Turning to Kant

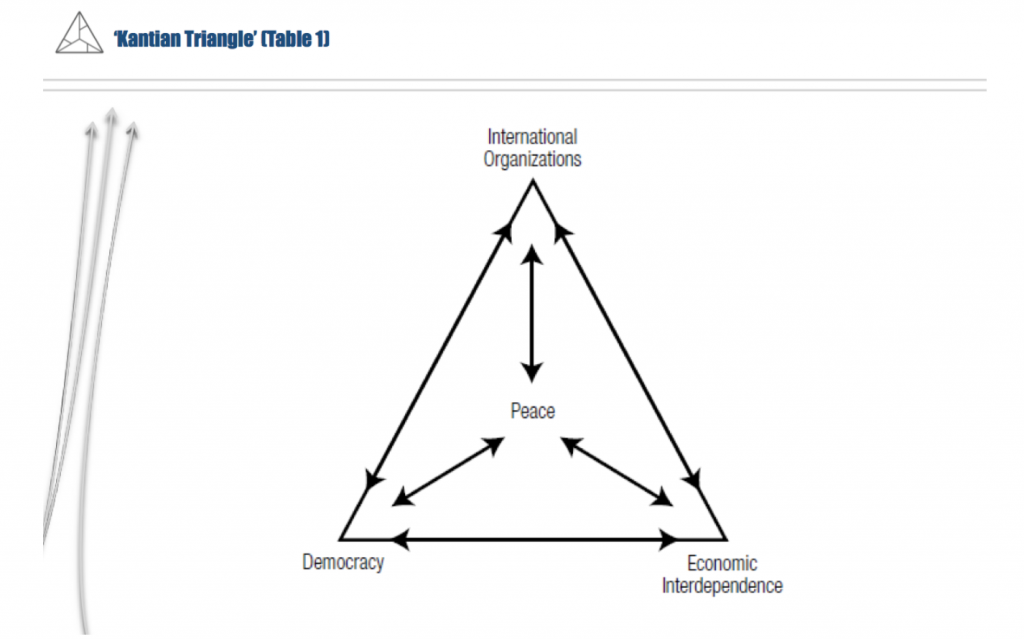

Change is the only constant in life – but it is for us to decide whether to change for the good or change for the worse. If there is one thing we know is that states have failed to channel the COVID-19 pandemic into a transnational agenda, worthy of reshaping global cooperation like we have never seen before. Instead, they brought us into a world fuelled by indifference, blaming games, rivalry, and even xenophobia. This world of chaos is what liberal philosophers, specifically, “Montesquieu, Adam Smith and Kant thought to be the natural conditions”. Perhaps, just perhaps, the pre-pandemic world we are mourning over is doomed to evaporate, and the post-pandemic world we are dreading about, on the other hand, is always meant to be the unfortunate reality we are forced to deal with. Indeed, we should be worried about our future in this post-pandemic world – with democracy faltering, the already-brim power of international organisations denied and economic ties cut, this is what Kant, according to the triangle he proposed, would argue to be an imminent threat to peace.

COVID-19: A Power Pandora’s Box

Leaders’ thirst to redefine and consolidate power over their respective regions have reared their ugly heads during this post-pandemic period. While the rest of the world, with widespread violations and resistance within respective countries, struggle to put social-distancing measures in place, China’s authoritarian government, for once, is admired for its remarkable progress in flattening the curve, and applauded for its unparalleled ability to swiftly and effectively impose lockdown measures. Democracy, as mentioned by the New York Times, is now perceived by many, a major roadblock and a trade-off to “efficiency” when it is the most needed in times of pandemic. The truth, however, proves the exact otherwise. A very recent research done by Frey, Chen and Presidente found that “democratically accountable governments, although introducing less stringent lockdowns than autocratic governments, were 20% more effective in reducing geographical mobility at the same level of policy stringency”.

While democratic strategies, such as “transparency, free flow of information” and legitimacy have proven themselves far more effective than autocratic tools, even in times of the COVID-19 pandemic, some leaders in various parts of the world are slowly engulfing power on the pretext of fostering efficiency and protecting public interests in general. The President of Russia, Vladimir Putin, for example, as BBC explained, “delayed public vote due on 22 April to a ‘later date’, a policy claimed by President Putin to “safeguard health and safety of the public”, but in effect, “gives him the right to serve two more consecutive terms”. In another case, as HRW noted, “Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisiss downplayed the coronavirus threat for weeks…, expelled a Guardian correspondent and ‘warned’ a New York Times journalist after their articles questioned government figures on the number of coronavirus cases”. As these leaders celebrate their proactiveness and altruism in defending public interest in the midst of this COVID-19 pandemic, the truth is that they are assuming power for their own self-interests. Leaders no longer serving the public but themselves, leaders no longer objective but subjective – these are the origins of threatened peace, watersheds in the history of war. Democracy perverted, peace shattered.

Solidarity no more

International Organisations, specifically the United Nations, since its inception, endeavours to “maintain international peace and security” – this mission of the founding members is neither of institutional or domestic capacity. It is, inherently, a transnational vision, hence requiring collective effort. Due to the macro-environment and global climate after the tragic Second World War in 1945, the victors, who were then, (and arguably still) the strongest powers, were granted preceding power in the Security Council. Since the Security Council was by far the most influential council of all in the U.N., and that decision-making on the most important matters were to be centralised and accomplished in this council, granting paramount power to the five permanent members was then considered proportionate and justified. The effect of this composition of the Security Council, however, is to be felt for decades to come.

For decades, the veto power has been used by states to object any matters of conflict of interest, sometimes resulting in deadlocks. Most notably, the United States, aligning its foreign policies with Israel, once, as the Reuters recount, “vetoed a Kuwaiti-drafted U.N. resolution that condemned Israel’s use of force against Palestinian civilians”. U.N is also highly financially dependent on major powers. With the United States responsible for “22% of U.N’s operating budget” , the U.S, along with other member states’ delay in delivering its dues in both 2018 and 2019 was said to have nearly put the U.N in serious financial trouble. In this sense, the United Nations, owing to its dependence on major powers for legitimacy, approval and financial input, lacks true enforceable power.

As the World Health Organisation is now slammed for its alleged support for China during the COVID-19 pandemic, President Trump of the United States “announced the severance of all US ties with the WHO late in May”. United Nations, and its respective agencies, innately, require solidarity from specifically, the major powers. With the withdrawal of one of the most important member states, its significance is further denied, its power is further stripped. We are, therefore, putting ourselves in an increasingly competitive world. A post-pandemic world that has no place for open dialogue, mutual understanding and cooperation.

Ties no more

Economic interdependence is made possible by mobility and to a certain extent, “free movement of goods” brought about by globalisation. As taken for granted as it is, COVID-19 is seriously upsetting this economic order – an order vital to incentivising cooperation and the sustainability of economies around the world. According to OECD, “COVID-19”, by putting mobility to a halt, “could cause 60% decline in international tourism, up to 80% if recovery is delayed until December”, where “tourist-centric countries”, such as Spain would be one of the hardest hit. COVID-19, on the other hand, by impeding trades, have “disrupted global supply chains”. Just as in the case of the financial tsunami in 2008, it will take years to revive and resuscitate the economy. As such, uncertainty is now clouding over major trade conflicts, specifically, the U.S.- China Trade War and even “India’s boycott of Chinese goods“. In face of this bleak and dire economic outlook, further rivalries and protectionist economic policies are to be expected. Ties cut, peace uncertain.

Combatting Chaos

With internationalism in such a prevalent crisis, it is more important than ever that the global community seeks a better, more sustainable path forward. While a sphere marked by political polarisation and severe pluralism makes incredibly hostile grounds for forging a coherent grand strategy, multilateralism holds the key to not only restricting the dangers of this international environment, but forging a more hospitable one. Global governance must change, it must be amalgamated and decentralised. Amalgamation in the sense that any initiative must be aligned in a way that the elite actors, mid-tier and grassroot interact via each other to achieve incremental security objectives. At the same time, no level of actor can have too much control or presence over another. They must interact informally, adhering to the instructions and advice from other parts of the system. Further though, international efforts can no longer rest with one domineering power at the helm, they must be decentralised. Decision making should be compartmentalised and organised within a coordinated, multilateral network of actors. As Drezner, Krebs and Schwiller note: Foreign policy must be able to appreciate regional knowledge and trust expert feedback to handle trouble spots, emergent problems and defuse crises before they metastasize (2020). Such a framework would be far more adaptable to the challenges of today’s world, fluid in the face of great power competition that for too long has necessitated miscalculations and failed agendas.

The Coronavirus Critical Juncture

As the world’s enchantment with American exceptionalism fades while Washington continues to abruptly abandon its leadership role, there could be an unexpected upside — a status quo upheaval. Catalysed by the pandemic, the world is quickly approaching a critical juncture. A juncture where we could see a systemic transformation from a top-down liberal order to an equitable system of global governance. Some such as Hathaway and Shapiro or W. Nordhaus argue that this can be done through the establishment of ‘Global-Governmental Clubs’. Such systems would incentivise gains on international public goods such as reducing carbon emissions or preventing nuclear proliferation with a simple ‘carrot and stick’ process. As put by Nordhaus:

(Nordhaus, 2020)

The main point here is that as our international cooperation efforts at present are failing for reasons of free-riding and deadlocks, the actions that lead to such outcomes in these club systems are punished, all while cooperation is rewarded. In these times of uncertainty, international dysfunction and institutional failure, we need to restore confidence in global leadership by breaking the system that allows inept leaders into power. We should not mourn the passing age but instead look to shape the post pandemic world in a more equitable form.

References

AL MESBAR Studies and Research Centre (2018). How national identity will shape the future of liberalism: The consequences of Brexit in the EU, and of the 2017 crisis in the GCC. Al Mesbar Studies and Research Centre. [online]. Available at https://mesbar.org/national-identity-will-shape-future-liberalism-consequences-brexit-eu-2017-crisis-gcc/. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

BBC. (2020). Coronavirus delays Russian vote on Putin staying in power. BBC. [online]. Available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-52038814. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Borger, J. (2020). Trump announces US to sever all ties with WHO. The Guardian. [online]. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/may/29/trump-who-china-white-house-us. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Campos, R. (2018). U.S. vetoes U.N. resolution denouncing violence against Palestinians. Reuters. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-israel-palestine-un-vote/u-s-vetoes-u-n-resolution-denouncing-violence-against-palestinians-idUSKCN1IX5UW. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Dowdy, Z.R. (2019). U.S. pays $563 million, part of dues owned, to United Nations. Newsday. [online]. Available at https://www.newsday.com/news/world/united-nations-dues-owed-1.39158123. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Drezner, D. W., Krebs, R. R., and Scweller, R. (2020) ‘The End of Grand Strategy’. Foreign Affairs. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2020-04-13/end-grand-strategy (Accessed: 3rd July 2020).

Frey, C.B., Chen, C, Presidente, G. (2020). Democracy, culture, and contagion: Political regimes and countries’ responsiveness to COVID-19. Covid Economics 18, 15 May, 2020. CEPR Press. Available at https://cepr.org/sites/default/files/news/CovidEconomics18.pdf. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Fukuyama, F. (2020) ‘The Pandemic and Political Order’. Foreign Affairs. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2020-06-09/pandemic-and-political-order (Accessed: 2nd July 2020).

Maqbool, A (2020). Coronavirus: The US resistance to a continued lockdown. BBC. [online]. Available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52417610. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Morello, C. (2019). Trump shrugs as U.N. warns it’s about to run out of money. The Washington Post. [online]. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/trump-shrugs-as-un-warns-its-about-to-run-out-of-money/2019/10/09/568f8756-eac5-11e9-85c0-85a098e47b37_story.html. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Neufeld, D. (2020). Visualising the Countries Most Reliant on Tourism. Visual Capitalist. Available at https://www.visualcapitalist.com/countries-reliant-tourism/. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Nordhaus, W. (2020) ‘The Climate Club’. Foreign Affairs. Available at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-04-10/climate-club (Accessed: 5th July 2020).

OECD (2020). OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). Tourism Policy Responses to the coronavirus (COVID-19). Available at https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/tourism-policy-responses-to-the-coronavirus-covid-19-6466aa20/. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Oramah, B. & Dzene, R. (2019). Globalisation and the Recent Trade Wars: Linkages and Lessons. Global Policy, 10(3), pp.401–404.

Petersen, H.E (2020). Indians call for boycott of Chinese goods after fatal border clashes. The Guardian. [online]. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/18/indians-call-for-boycott-of-chinese-goods-after-fatal-border-clashes#:~:text=Indians%20call%20for%20boycott%20of%20Chinese%20goods%20after%20fatal%20border%20clashes,-Indian%20officials%20plan&text=Indians%20have%20called%20for%20a,soldiers%20dead%20and%2076%20injured. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Rodrigues, M.A.V (2017). Democratic vs. efficiency: how to achieve balance in times of financial crisis. Rev. Adm. Pública vol. 51 no. 1 Rio de Janeiro Jan./Feb. 2017. Available at https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0034-76122017000100088&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en#aff2. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Roth, K. (2020). How Authoritarians Are Exploiting the COVID-19 Crisis to Grab Power. The New York Review of Books. Human Rights Watch. Available at https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/03/how-authoritarians-are-exploiting-covid-19-crisis-grab-power. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Russett, B.M, O’Neal, J.R (2001). Triangulating Peace: Democracy, Interdependence, and International Organizations. Foreign Affairs. [online]. Available at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/capsule-review/2001-05-01/triangulating-peace-democracy-interdependence-and-international. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Schmalz, F. (2020). The coronavirus outbreak is disrupting supply chains around the world – here’s how companies can adjust and prepare. Business Insider. Available at https://www.businessinsider.com/covid-19-disrupting-global-supply-chains-how-companies-can-react-2020-3. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Schmemann, S (2020). The Virus Comes for Democracy. The New York Times. [online]. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/02/opinion/coronavirus-democracy.html. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

United Nations (n.a.). What We Do. Available at https://www.un.org/en/sections/what-we-do/. Accessed on 4 July, 2020.

Waltz, K.N. (1962). Kant, Liberalism, and War. The American Political Science Review, 56(2), pp.331–340.