“I don’t need to learn Vietnamese because I don’t have to”, said Brian with his complacent attitude. Brian has been in Vietnam for more than 10 years, with a wife who is Vietnamese and a beautiful, cheeky daughter who will turn 3 years of age this summer. Vietnam has provided him with a flourishing start-up company, a well-grounded family, and an international network of friends, relatives, co-workers whose nationalities stem from all over the world. But despite all of those factors, he doesn’t feel the need to pick up Vietnamese as his second language. To him, there is an inherent pride vested in the fact that he can live on with his life just fine without having to know the language of the land that nurtured him.

A comment on a video showcasing interviews with Western residents in Japan, asking them if they can speak Japanese leaves a significant impact on me: “How can someone live in a country for that long and be incapable of speaking the language. I would have gone insane with the thought of not understanding everything that is happening around me.” After connecting the dots to Brian’s self-contented comment, something suddenly dawned on me, this action of Brian can’t be deemed as his fault. This is not an individual’s fault, but rather, a fault from the deceased, which dates back hundreds of years ago, when the French first came to colonize Vietnam in 1858, leaving devastating calamities, far-reaching and disastrous impact on the country.

As long as there are racial privileges, racism will never end.

Wayne Gerard Trotman

A History of Prohibition and Colonial Bloodshed

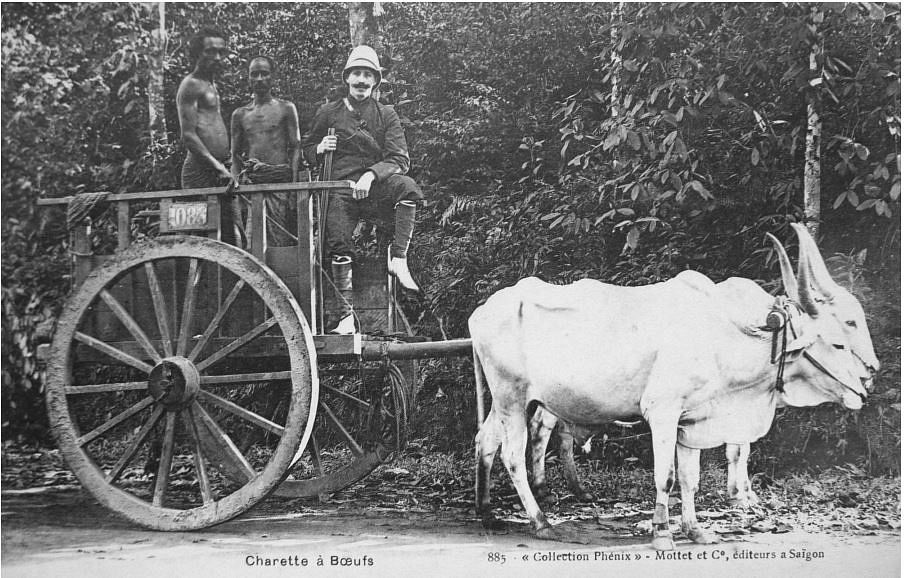

After the French and American army left Vietnam, they haven’t done it without a parting gift: blatant xenophilic advertising, which later on gradually resulted in a heightened sense of value towards Western commodities among the Vietnamese upper-class community. And for the most part, its consequences can be seen from an inextricable link to our attitude toward foreigners today, blind worship and praise of their every movement in cognition, giving them the pedestal platform to look down upon culture, language, and heritage. This doesn’t happen overnight, however, but an underlying pattern laid upon our mindset for decades, fueled by colonization and thus, a heavy dose of exoticism and western centrism, usually serve to reinforce an imperial gaze upon western otherness.

To understand this kind of behavior that millions of Vietnamese are now leaning toward, we must go back several centuries when rice wine was, and still is an integral part of Vietnam’s social traditions, economy, and culture. Examining its history not only provides insights into the rapidly changed attitude of Vietnamese towards foreigners, but also how westernization has evolved and ingrained in people’s minds for thousands of years and up until this very day.

Rice wine is a distilled liquor from Vietnam, made of either glutinous or non-glutinous rice. It was formerly made illegally and is thus similar to moonshine. It is most typical of the Mekong Delta region of southwestern Vietnam. It held a significant position in many traditional activities, as a staple product in Vietnamese villages for centuries, with both practical and ceremonial values. When the nation consisted mostly of rural villages and small towns, men and women consumed it before going into the fields, at lunch, and with dinner. Moreover, during engagement ceremonies, historically the groom was required to provide the bride’s family with eight to ten jars of rice wine while on the wedding day the families shared a ceremonial cup together.

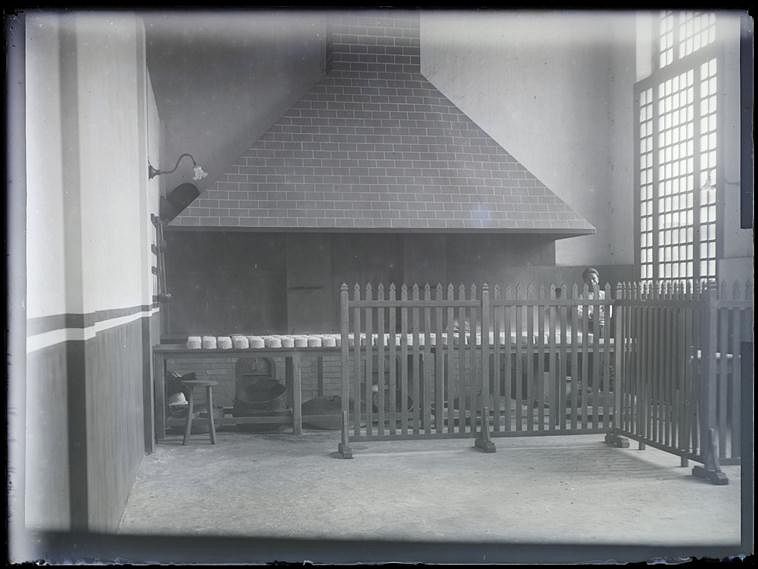

During the colonial period, the French would use rice wine as a means of controlling their dominance of Vietnam. Heavy taxes and government control established in 1897 have been implemented in order to diminish the value of rice wine on the market. By the end of the 19th century, the colonial government had established a complete monopoly on the production, distribution, and sale of rice wine. When France was first establishing a colonial presence, its drinks became a representation of wealth and modernity, much like everything else that is supposed to be perceived as fancy today such as the new iPhone or a pipe of tobacco. For that reason, Vietnamese are eager to embody a sense of modernity by embracing foreign alcohol over rice wine.

Since the country first opened to global markets in the 1990s, people began having eyes on the new products flooding in, including the extravagant Western beer and wines. This is coupled with the fact that the average young person in Vietnam doesn’t have that much fanciness towards rice wine. It now remains a thing in the past, unmarketed and relegated to crude vessels in countryside homes.

While rice wine production still persists among rural areas, the number is declining. And as the country continues to urbanize and city dwellers show little interest in traditional products, it’s hard to be optimistic about its future.

Vietnamese products are perceived as ‘boring, nothing new,’ and consumers are not assured of the quality.

Le Thanh Truc, a woman who set up a rice wine operation explains

Western Centrism In a Can

While the traditional food in Vietnam often deemed as interesting and delicious, such as phở, spring rolls, or bánh bèo and hence their status of being unique to the culture serves as a culinary attraction in the eyes of foreigners, there is no denial on the influence of French colony past in the making.

The appearance of canned sardines in Vietnam dates back to when the country was still a French colony. In the book Appetites and Aspirations, author Erica J. Peters notes that canned and frozen food is the main food for French soldiers while in Vietnam. At that time, the French colonialists refused to eat local agricultural products, despising Vietnamese white rice, fish sauce, and street food. Hence, in the effort to differentiate themselves from the locals, the French turned to expensive canned foods such as vegetables and meat, and especially canned sardines to emphasize their dominant high status apart from the mucky locals.

Canned sardines were popular among the French and were popular for their convenience, typically working-class people would keep tins of canned sardines for when they didn’t have time to cook. The most popular type of canned sardines was packed in tomato sauce, which was also the cheapest at the time. These canned goods also reached the Vietnamese middle and upper-class while serving as a representative of the epitome of European goods consumption among Vietnamese people in the 20th century. And although refusing to eat the food that their colonized land offered, the French colonists seemed to not mind their sardines being harvested from Morocco, a country that became a French colony in 1912.

Working-class French people and Vietnamese living in the country and overseas all share a page in history about canned food, and sadly, it’s a page where the more powerful party wields the pen. A bitter taste of the past, and a path to the harrowing xenophile future.

You might eat Southeast Asian food weekly without ever really being confronted with the realities of Southeast Asian lives.

Elaine Castillo – Colonialism in a Can

Imperial Gaze and Western Imaginations

This takes us back to Brian’s situation, more nuances are hiding underneath the surface more than we would want to admit. Understanding the history behind his story will not only provide insights into the neglected action of one individual among the community but also, raising awareness about a notion that is exacerbated by racist concepts of white supremacy that have been ingrained in Vietnamese’s people minds for decades.

You can find this kind of nonchalant sentiment appearing ubiquitously not only in Brian but among expatriates who have lived and worked here for most of their lives. Businesses and corporations have taken a trend that eerily reminds us of the colonial period, in which they would eulogize western workers regardless of the context, and view other non-western ones as expendable. This cruel reality, however, seemed to matter little to the colonizer descendants, while the rest of the population suffer from abysmal working conditions and meager living wages, they are living to the fullest with their extravagant, affluent lifestyles, even receiving broad admiration from the natives when performing elementary act such as speaking simple phrases in Vietnamese.

For example, recently, in an entertainment program on television, when a foreign contestant who has lived and worked in Vietnam for seven years, spoke and sang in Vietnamese very well, but was still being forced by a judge to communicate in English just because it sounds more “expensive” that way. More broadly, while some foreigners coming to Vietnam have a sense of learning to speak and write Vietnamese in a standard, unadulterated manner, some still consider it’s unnecessary to do so. The fact that you are white and can speak English is a good enough reason for you to receive respect from the locals and earn you a higher paying job than most of Vietnamese’s standard living wage. So why bother learning the language in the first place, when you can live just fine with what you already have?

The foreign-educated system dilemma

The dilemma of Vietnam’s foreign-educated system has led people into frustration. As students in the country nowadays are becoming more and more attracted to studying abroad at universities in the United States, Canada, Australia, and across Europe, more Vietnamese families have invested in overseas education for their children. In 2015, according to reports, Vietnamese families spent roughly US$3 billion on their children’s education and training in 47 different countries. A report made by the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement also stated that as of 2019 November, there were 30,186 international and exchange students from Vietnam attending American schools and universities. Meanwhile, the Australian Embassy in Vietnam triumphantly proclaims Australia as the most popular English-speaking destination for Vietnamese students and researchers.

This trend of studying abroad has created a myriad of new opportunities for study abroad agents, English tutors, and learning centers appearing at a rapid speed all over the country. As an increasing number of Vietnamese students head overseas for their education, so are the numbers of English learning centers and English tutors that offer hope for a foreign future. A recent report by state-owned Xinhua news agency said two-thirds of the 400,000 foreigners teaching in China in 2017 were unqualified, with some also working on fault visas, and this number is not far from reality when it comes to Vietnam. No one asks about the qualification of foreign teachers, the degrees and certificates they have, and whether they have teaching permits, despite these being important information. And the reason why is because of race, English teachers with white skin color are much better paid than their colleagues with black skin. If you’re Caucasian, have a pulse, and all your teeth, you’re guaranteed an English teaching job in Vietnam is a running joke in the English as a Second Language (ESL) circle. And that’s not the end of it, it is easy for foreign language centers to attract students if they advertise that they hire foreign teachers from “white” countries, which means that the discrimination is beyond not just for Black employees, but for all the English teachers that do not have the white skin color, and that’s including the one that was born in Vietnam.

Racism is very subtle, very institutionalized. At least when you have obvious racism, you can name it, challenge it, you know what you’re up against.

Angela Onwuachi-Willig, a law professor who teaches critical race theory at the University of Iowa.

Prejudice in Vietnam comes in many colors and has evolved along with the country’s dark history of colonization. “The idea of race is a modern phenomenon,”, according to the 2013 book Race and Racism in Modern East Asia: Western and Eastern Constructions. It’s a social construct that exists in people’s minds and has been exacerbated over time by the wrongful mindset of the predecessors. Vietnamese might not come out and say they admire white people, but the sentiment appears when they apply to lighten skin creams, pull on socks underneath their sandals, or drive with arm-length gloves to appear whiter than they should be.

While the French played a role in shaping 20th-century prejudices in Vietnam, the transient ex-pat population is helping to determine today’s racial attitudes in the country. Western teachers have been known to get hired simply because of their skin and dark-skinned foreigners are often looked down upon, with some Vietnamese linking their skin tone complexions with poverty. There is no denying that the existence of racism among the country’s citizens is there but unlike Western countries when white supremacy appears among white citizens, white supremacy in Vietnam works in a very mysterious way that leads them to believe that white people are superior to their own people.

As the nation modernizes, leading to an increasing number of people moving to urban centers, looking forward to a more lucrative and convenient lifestyle, dismantling the potency of ritual where they hail from, colonialism’s legacy is still here to stay, and it shows no sign of leaving any sooner.

IVolunteer International is a 501(c)3 tech-nonprofit registered in the United States with operations worldwide. Using a location-based mobile application, we mobilize volunteers to take action in their local communities. Our vision is creating 7-billion volunteers. We are an internationally recognized nonprofit organization and is also a Civil Society Associated with the United Nations Department of Global Communications. Visit our profiles on Guidestar, Greatnonprofits, and FastForward.