In a country like India where arranged marriages are still the norm, the dowry system benefits highly from its other quagmire: the fair skin hullabaloo. As a girl in the Indian marriage market lugs from light to dark in the skin palate, her prospective array of grooms shrinks, and the dowry bag bloats up. It’s quite like a mathematical equation in that this is often taken for granted by the populace (RIP, logic). Especially in rural areas of India, there are few voices that can rise against such ‘norms’.

As human beings, we are involuntarily trained to accept and naturalize conditioned schemes and constructed ideals. There comes a time in history wherein we are unable to even recognize the constructed-ness of (almost) all the things we take for granted. For instance, for the longest time, we have been taking the patriarchal order for granted until countercultural questions began to uproot many of its constructed notions. While the past couple of centuries have been largely about incoherence and nonconformity with the dominant order, there are still certain areas in the world that are yearning for change. Developing spaces as India fall into this denomination. Being woke and challenging a custom is anything but a trend in rural India. Many lives and livelihoods hang in these strings. More often than not, lower and middle-class Indian fathers would be desperately praying for a son outside labor delivery rooms. If not, they make a bet with all the gods for at least a fair-skinned girl because marrying off a dark-complexioned girl before she expires in the marriage market is a life-and-death game. Fathers of daughters in India often have to toil their entire lives to get them married off to mediocre homes. Therefore, the privileges by birth not only confine to religion, caste and gender in India; it also extends over to the skin one’s born with.

India’s ‘Fair’ Drive

I once had one of my closest relatives who was about to get married tell me that she was looking for a ‘fair’ guy. Fair, in what sense? You’ll soon find out. When a man of brown skin approached her with a proposal, she politely declined. That they were not compatible is a valid reason. But she garnished it with an appalling statement. She said that marrying him would mean she’d have ‘dark babies’ and that eventually, she’ll have no other option but to kill them! I was a teen when this conversation happened and I am still as shocked as I was then. It was astonishing that she was saying this to me, a naturally brown-skinned girl. My first thought was whether this person would have murdered me because of my skin if she had the chance!

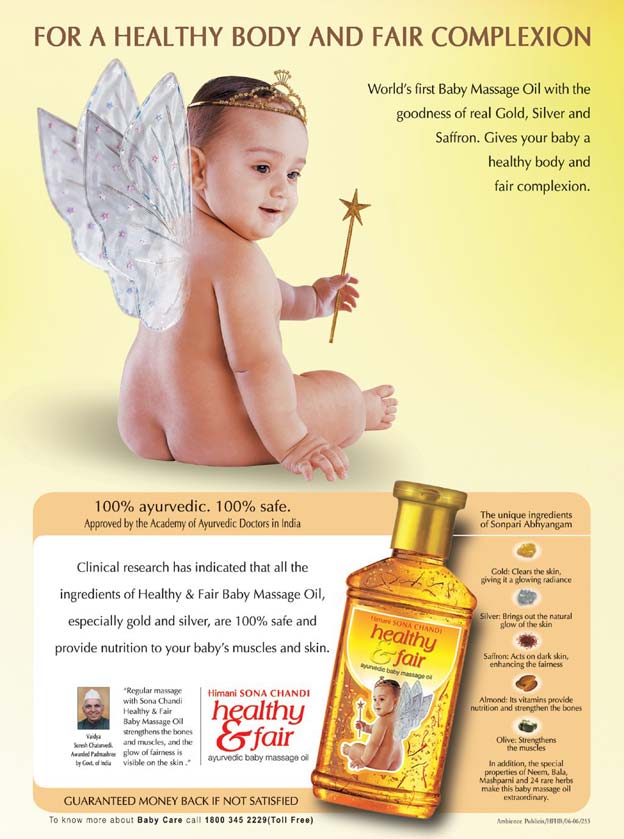

This is only one of the many superficially funny and logically excruciating things I was exposed to while growing up an Indian. You could call it our own homegrown system of colorism if you please. On a serious note, it is rather scary to admit that India sells not only fairness products (or fairness treatments as some of them like to be called) for young adults, but skin-lightening body rubs and oils for babies as well. It is almost a matter of shame even today for many middle-class, urban households to have a child on the ‘darker’ scale. But credit when it’s due; things are changing and young India is stepping up to combat this weird paradigm that has made many a life hellish.

When the popularity of the Black Lives Matter Movement began to escalate in the year 2020, India too was engrossed in this debate. Hindustan Unilever Limited’s infamous fairness product Fair & Lovely was beginning to face quite a lot of backlash on social media platforms for having made generations of Indians lose peace over unattainable and illogical beauty standards that are eerily similar to the ‘racial purity’ baggage which the British brought along with them in the 1600s. A product that began to problematize the idea of being desirable since 1975, Fair & Lovely waited a good forty-five years to address the fundamental stereotype over which HUL has been profiting. In 2020, the firm decided to drop the ‘fair’ from the product’s name and switch it with – wait for it – Glow & Lovely.

Now there are two sides to this debate. Some critics believed this was an outstanding move on the brand’s part because they also removed the ‘whitening’ and ‘lightening’ promises from its packets. They revolutionarily discarded the skin shade card from their advertisements that previously showed actress Yami Gautam climb the ladder of success as she climbed up the shade card to lighter skin tones. However, the new advertisements kept coming off as tone-deaf and appalling as they did before. The ads justified the change of name by saying that the product can now bring ‘more than brightness’ and give users ‘HD glow skin’. (Seriously, HUL?) How exactly do we define the journey from ‘fair’ to ‘glow’? Is this stunt by the brand anything more than a shallow pacifier to redirect the criticism it has been receiving? Let’s not even get started on how many actors who are active ambassadors of fairness products like Fair & Lovely spoke up in support of the BLM Movement on their social media.

The founding president of the Joint Women’s Dermatology Society and Indian Women’s Dermatology Society, Dr. Rashmi Sarkar says that as a dermatologist practicing in New Delhi, she consults at least 50 patients each month who seek solutions for their dark skin. In the study conducted by H. Shroff, et. al. titled Skin Color, Cultural Capital and Beauty Products: An Investigation of the Use of Skin Fairness Products in Mumbai, India, it was found that 40% of the population in Mumbai extensively use skin lightening products. These products are used by both men and women in India. The research study by Samara Pollock, et. al. elaborately studies the underlying evil surrounding the skin lightening industry of the world and validates how various dermatologists are against the prevalence of such products. This backlash is triggered not only by the myths surrounding fair skin but also due to the potential health hazards the chemicals could induce upon young adults.

Colonial Residue or Deeper Evils?

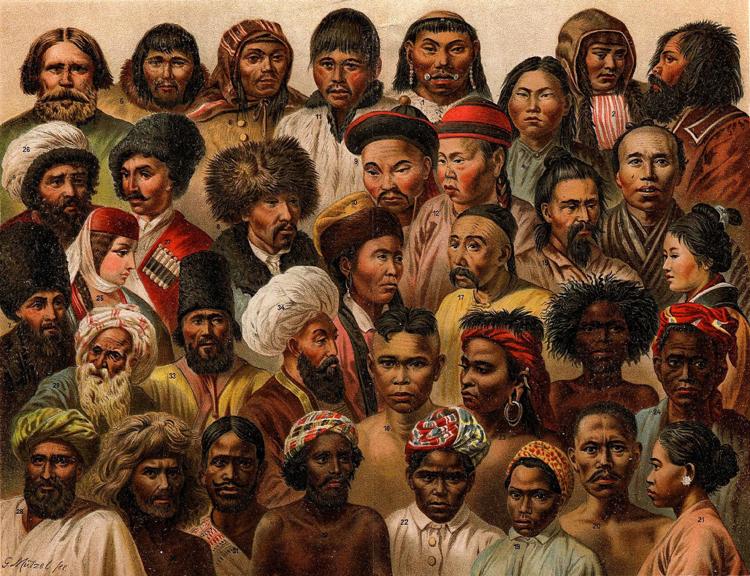

India’s unique cultural composition is a rare instance of fraternal unity. Sure enough, this does not come without its occasional (or recurrent, in the current times) debates on communal conflicts. But we’ve somehow managed to avoid another partition since 1947. However, with such vivid diversity, we also run the risk of occasional relapses and instances of incoherence. To reduce the color craze that has been making its waves in India as simply being a colonial hangover may be too easy an explanation. The casteist racism that has been prevalent in India ever since Manu (who wrote the questionable Manusmirti) has a lot more to do with this than we would like to accept.

For a long time now, India has been buying into this narrative that the tiered caste system is a hierarchical model prescribed on the basis of occupational, economic, and social standings of individuals and/or lineages. The genetic (hence, racial) aspect of the caste system often had to be squeezed out from between the lines. A recent study, conducted by the National Institute of Biomedical Genomics (NIBMG) located in Kalyani, West Bengal, found from the DNA samples collected from various communities in India that the intermingling and intermarriages between the population groups came to be prohibited sometime around the Gupta period of 1600 years back. The laws passed during the period curbed inter-caste marriages and the blending between population groups of varying genetic and ethnic compositions. These findings have been published in the National Academic Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS). What these vital conclusions prove is that caste, at the end of the day, has an intrinsically disguised genetic root to its foundation and needs to be studied beyond its peripheral vocational justification. Racism, therefore, is an important aspect of the caste system in India and Manu becomes the leader of our local Klu Klux Klan!

Casteist Connotations

Dalit (a term commonly used to refer to those from the ‘lower’ and underprivileged classes of society in India) scholar Rohith Vemula of the University of Hyderabad committed suicide in 2016 due to the caste-based discrimination he faced from the institution and society. His demise was a wake-up call to India wherein caste differences had been naturalized and apparently remedied by reservation policies. India was suddenly faced with the compulsion to confront the villain of race it has been trying to sideline for so long. Left-wing political parties were compelled to bring a novel ‘caste-based’ perspective alongside their class-based norms and ideals. The Indian National Congress could not afford to belittle these discriminated groups of people into convenient ‘vote banks’ and had to address legitimate issues faced by them. And probably one of the most important changes that took place was the growing influence of the Ambedkar Students’ Association (ASA) in the campuses in India, which was an abode for Dalit and underprivileged students to voice their protests.

There is much more to this narrative than what meets the eye. The nation has mutated its vision into colored perspectives. Varna (literally translated into color), which is a concept defined in the doctrines of Hinduism, differentiates people into classes including the Brahmins or the priestly population, the Kshatriyas or the administrative population, the Vaishyas or the artisan/tradesmen population, the Shudras or the wage-earning labor population and the ‘untouchable’ population of tribes. Very reminiscent of the apartheid system, differentiating groups of people on the basis of their vocations and color is a criterion employed by the hegemony to group them into thousands of jatis or castes.

Long story short, with independence, the Constitution of India allowed for the betterment and empowerment of the marginalized castes among people. The reservation system of the country addressed the relegation of many disadvantageous groups of people by offering them representation in educational, employment, and political sectors. Although this has brought about some desirable unrest to the pyramidal structure preferred by the classist order, India still has a long way to go in order to establish proper equality. However, the dominion continued to prefer the segregation in the society for obvious reasons; it ensures them power, wealth, and better societal standings. Colour eventually became a criterion that overtook the occupational exemplar. Although the topic at hand is way more complicated and interlaced than this, color indeed became a significant aspect for segregation among individuals belonging to different castes/classes. The study conducted by Dr. Kumarasamy Thangaraj of the CSIR – Centre of Cellular and Molecular Biology or CCMB, Hyderabad in association with Estonian Biocentre, Estonia, concluded that India’s caste system and its segregational paradigm has a ‘profound influence on skin pigmentation’.

The Perfect Union of Casteism and Colorism

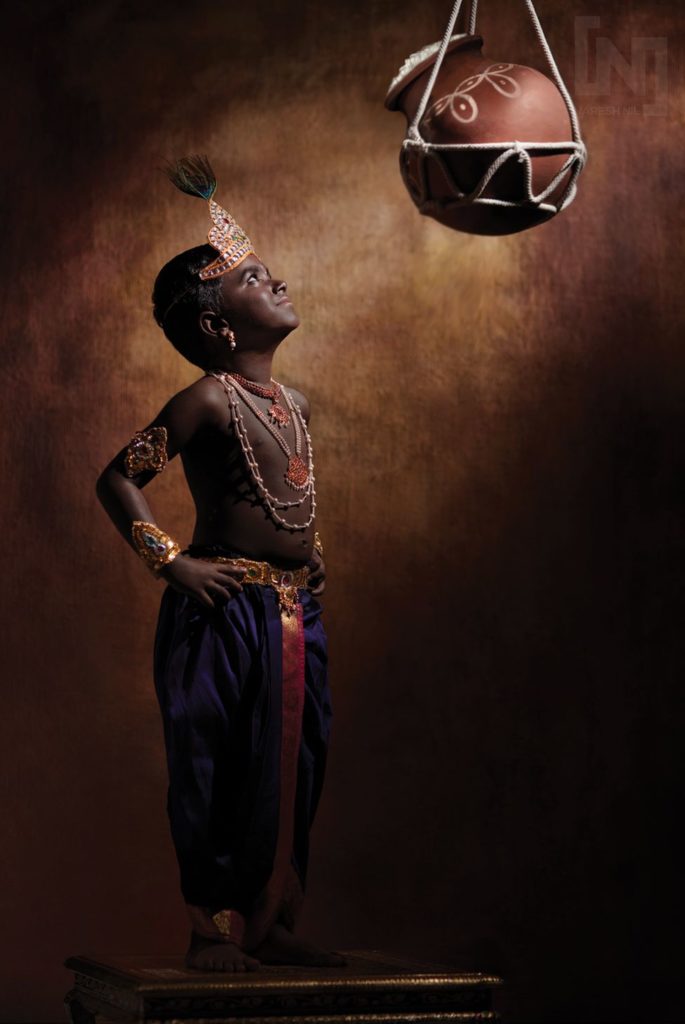

White supremacy’s advent in the Indian subcontinent can be clearly noted in the modern renditions of the mythologies from the country. The hero of the epic Ramayana, Rama was defined to be as ‘swarthy as the blue lotus’ by the saint-author Valmiki. He depicted Ravana, the villain, as a ‘mound of black collyrium’. Similarly in other mythological texts, Lord Krishna is described to be as dark as rainy clouds. In fact, his name literally translates to ‘black’. However, these gods suffered exactly what Jesus suffered in the hands of the European ethos; they grew pale. Strangely, Krishna began to be depicted in blue just to avoid the internal conflict which could be ignited upon witnessing a dark god. With the Aryan invasion of the subcontinent, the relatively darker-skinned Dravidians who were the natives began to be looked down upon. For invaders of the land, ‘Hindu’ as a term formed the depreciated acknowledgment of the natives. This later evolved into the religious structure we know today while maintaining the racial apartheid.

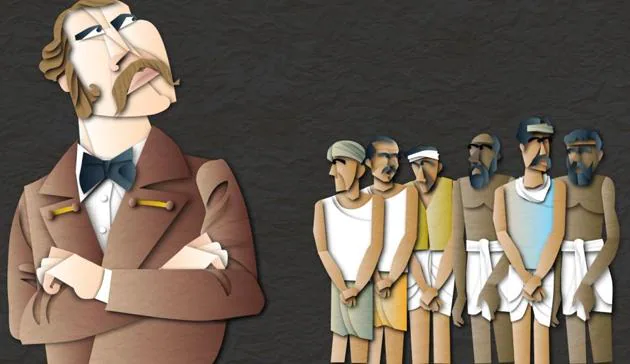

The British gained much from maintaining caste and religion-based segregation among the natives in India. However, the racist promulgations cannot be limited to colonial and post-colonial periods. They surely served as incentives for the maintenance of the system. But, the English were not the only ones responsible. Contemporarily, the obvious preference of white over black can be narrowed down to an essentially colonized intellect. Intellectual colonialism is one of those tropes maintained by the superpowers to keep yesteryear dichotomies alive but subtle. India records multiple occasions of African students and tourists being attacked and discriminated against in educational institutions and other places. Such events place the problematic postcolonial conscience in the ‘white-man’s-burden’ shoes wherein the average Indian takes it upon themselves to ‘tame’ and/or ostracize the ‘barbaric, dark-skinned savages’. This internal division is simultaneously countercultural and counterproductive!

The Fairness Industry of the East

In popular culture, this confusion can be traced in multiple instances. The 2019 Hrithik Roshan starrer film Super 30 had the actor dipped in bronzer to convince viewers of the Bihari mathematical genius he was portraying. The story was meant to portray the journey of Anand Kumar, the educator based in Bihar, whose rags-to-riches biography is beyond inspiring. The effort put in by the filmmakers to make Roshan, who is dubbed as India’s closest bet to a Greek god, appear tan (and hence, apparently, poor and struggling) was met with much backlash. This was, however, not Bollywood’s isolated instance of racial appropriation. Whether this is entirely racist or elitist is up for debate. However, the bronzer problem can be read in lines with the ‘black face’ conundrum in Hollywood.

Before the BLM Movement served to complicate the fate of fairness products in Indian in 2020, the country’s fairness industry was expected to hit the ₹5000 crore mark by 2023. In 2019, this was at a whopping ₹3000 crores! According to a 2019 study by the World Health Organization, skin whitening products make up for more than half of all of India’s skincare products. Asia’s skin lightening is estimated to be worth $7.5 billion. The global skin whitening market is valued at $13 billion. Asia singlehandedly constitutes more than half of this. According to a report by Francesca Regalado, 40% of the sales in Asia is China’s contribution, followed by Japan (21%) and South Korea (18%). However, some level of skepticism has begun to find ground regarding its racist undertones especially after the global retorts against white sovereignty. Amongst popular brands, L’Oreal and Johnson & Johnson were the first to denounce promises of ‘whitening’ on their product packages. Kiyokazu Shibukawa of the EY Advisory and Consulting, Tokyo, validates that India and Southeast Asia are the few regions where the whitening market still finds unwavering support.

As we talk about the fairness hysteria of the east, few seas across in the west, the color of one’s skin is an indifferent terrain that is selectively and simultaneously problematized and belittled.

Meanwhile in the Occident…

Dark skin has been through one roller-coaster of a ride through the ages. Although violence and prejudice against black and brown people still survive in the ‘fair’ empire of the West, darker shades of skin have come to represent different notions for the white kin today. Thanks to Coco Chanel, sun tanning is accepted as Hollywood’s symbol for exoticism and adventure. The fashion world of the West has, since the early 20th century, transformed yesteryear’s stigmatization of darker skin into a hallmark of wealth and somehow, miraculously, still achieved to keep the prejudice intact. The apparent residue of this prejudice still rules its former colonies in the east.

What darker, tanner skins are representative of has evolved over the years. This evolution, without a doubt, has been manipulated with and shuffled around by the ‘superior’ white race. Today, having tanned skin is perceived differently by whites and the rest of the world. Strangely enough, the same has been rendered differently in different contexts by the whites alone. While it comes to establishing equal rights and abolishing discrimination, the color of a person’s skin holds a different significance. The same tone of skin color is digested to be suggestive of a constructed, romanticized notion of an ‘exotic’ holiday at the beaches in other instances.

The very history of black oppression is rooted in the binaries drawn between lighter and darker shades of skin. This was denotative of the labor African-Americans performed in order to survive. The upper-class aristocrats, who went on to script the horoscope of the impending capitalist world, cherished their pale skin. White skin meant no labor and therefore suggested wealth, sophistication, and more wealth. Black people were slaves, laborers, and ‘uncivilized’ barbaric beings whose vicinities were avoided by the wealthy whites; especially white women. The melanin in their skin was, therefore, a collective consequence of the land of their emergence and the labor they undertook to survive.

Time passed and eventually, capitalism came to consume the world. Colonies were formed, demolished, and re-formed. The World Wars too changed how things were perceived. But what each milestone did was to ensure that capitalism was here to stay. The understanding of darker skin colors (brown and beyond) too began to change. However, the prejudice remained intact with little concessions like the abolishment of slavery. With years, darker shades of skin began to be associated with wildness and adventure. Whatever was previously imbibed to be the lack of ‘white enlightenment’ and ‘white culture’, began to exist among the markets as a commodity. The idea of commercializing tan skin was instigated roughly with Coco Chanel’s much-popularised skin tanning voyage in 1923. This was the transition tan skin made from being perceived as ‘uncultured’ to being ‘wealthy enough to have vacations by the beach’. Tanning oils, sunscreen firms, and even suntan Barbies came into sale. While Europe’s previous colonies like India sold fairness creams in bottles, their colonial mother had taken to selling darker skins in bottles and spray tanning salons. This meant that the white folk could have black skin without having to face the turmoil of being black in ethnicity and its repercussions. Similarly, hairstyles like cornrows that are innate to the African culture began to be commercialized as were their accents and slangs. The conscious adoption of such cultural entities is debatably the appropriation of black culture, without paying due respect to their history. In popular culture, we term this as ‘blackfishing’.

Blackfishing

In 1614, John Rolfe, an early English settler of North America wrote a letter to Sir Thomas Dale, He had met Pocahontas, the daughter of the Powhatan Indian Confederacy’s chief in Jamestown, Virginia. In his letter, Rolfe seeks permission to marry Pocahontas to fulfill his ‘duty’ of mastering the ‘uncivilized’ race and transforming the ‘savage’. The sexual union he desired with the exotic beauty is manifested as his fate ‘to labor in the lord’s vineyard (the woman’s body), there to sow and plant, to nourish and increase the fruit’, as Paul Brown questionably points out in his essay ‘This Thing of Darkness I Acknowledge Mine’: The Tempest and the Discourse of Colonialism. Rolfe advocated that by being betrothed to her, Pocahontas could be baptized through marriage, and hence, the native race could be ‘cleansed’. The exoticism and mystery associated with what was regarded as ‘savage’ races operated on two terrains; one, in that they were regarded as inferior, and two, in that they were considered as exciting and tempting. The second narrative completely ignores the political repercussions of the first.

The term blackfishing was first introduced by Wanna Thompson on Twitter in 2018. In her Paper magazine article, she wrote how the whites have been craving access to blackness without the legacy of suffering that constitutes its mold. Celebrities ranging from Kim Kardashian to Jesy Nelson are repetitively being notoriously accused of blackfishing. In spite of it being called out ritualistically, it has begun to become somewhat of a norm to appropriate the black culture, face some backlash for it and receive negative publicity (which is still publicity). The aspiration to appear black may be narrowed down to the desire to appear ambiguous and mysterious and therefore, exotic and fresh. There is an unwritten aura of boredom associated with the privilege of white skin. Thus, adding a pint of brown and some cornrows or changing that dialect of speech will keep people guessing for longer. Many justifications of blackfishing surround the idea of embracing a hitherto marginalized culture and bringing it over to the mainstream. Thompson, however, records this as a ‘dangerous paradox’ that relieves the whites from experiencing anything remotely catastrophic as the black history and still have access to the exoticism associated with it.

(Blackfishing) is like blackface, albeit a version updated for the digital age.

Mikki Kendall (‘Jesy Nelson will dispose of her Black costume when it no longer serves her‘, The Guardian)

The Fake Tan Business

During the ongoing pandemic, the global sunless tanning market was estimated to hit $1.8 billion by 2026 according to the Sunless Tanners – Global Market Trajectory & Analytics 2021. These statistics are furthered into deciphering that the US will readjust to 4.9% CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate). Nearly $12 million are deemed to be the future contributions of European markets, excluding Germany. Japan will likely take this to $71 million by 2026. It needs to be given due attention that the fairness and the tanning industries tend to co-exist in certain countries like Japan. Both of these industries, miraculously, do not cancel each other out and are booming in their own respective reigns. Where do we place the collective conscience of the populace in such spaces? More importantly, what do we make of the ideas and ideals with which youngsters are growing up in this global scenario?

Rosalind Gill, in her phenomenal work Postfeminist Media Culture extensively inspects the modern-day complications of what she deems as the Makeover Paradigm. The postfeminist media culture forces young women to believe that they should be reinvented or transformed in order to come off as desirable. This theory shall be extended beyond feminism and should ideally incorporate the larger schema of things wherein keeping up with a trend is of utmost importance. 21st century’s visual culture has served for the co-optation of every sensitive group merely to commercialize their marginalization. The fake tan business that has come to become an industry of its own runs on these constructed, capitalist conceptions that are myths. People of non-European descent are still persecuted for their skin color, thought to be uncivilized, and denied fundamental rights. What do we make of the white celebrities voicing their sympathies for George Floyd on Instagram alongside a brown-face selfie? We have a large group of privileged folk commercializing darker skin tones, marketing them, and appropriating their ethnicity and history in ignorance. While a group of people is made to feel inadequate for their tones, the others are relishing in the illusion their borrowed tones bring them. Not only are their labor and hardships looked through, but they are also romanticized enough to be commoditized.

As Asia still reminiscences over becoming fairer than the sun, while trying to avoid the sun, the ‘land where the sun never sets’ has already capitalized the sun in bottles, beaches and tanning beds! The question of debate shall take into consideration the various other facets of issues that are intrinsically aligned with colorism. In a cultural melting pot like India, the issues surrounding race are bound to the ideas of religion and caste that directly determine the fate of matrimonial unions and familial structures. Many young Indians grow up normalizing the notions of colorism despite the caste to which they happen to belong. In this dynamic era where global matters of concern are discussed widely on the internet, many voices of power continue to take a hypocritical stand in the guise of appearing woke and politically conscious. Reacting to sensitive issues are also performative acts today, wherein a person of significant agency would need to consult the popularity of hashtags and the possibility of making a headline before they react to an issue. In this age of scary surveillance and unquestionable agential power, the matter at hand melts into oblivion where the individual takes most of the spotlight.

Sure enough, popular culture makes heaps and loads of money out of keeping certain stereotypes and prejudices intact. Capitalism cannot profit from an ideal society. After all, more often than not, capitalism is playing for and against the same question of debate. They churn out red t-shirts in factories that endorse the ideals of socialism and sell them at $30 apiece. Mechanically produced commodities often advocate a rebellion against the mechanical production of commodities. We live in a time where magazines simultaneously endorse affordable plastic surgeons and publish a piece on embracing your ‘flaws’! This is reality as we know it. We might not be able to crystalize solutions out of all our problems but we surely are able to problematize them further. This is where better readings, contradictions, and counter-narratives come into the picture. It may not be entirely ‘fair’ to talk about the boom in the fairness industry of the east without acknowledging the growth in the tanning industry of the west because whether or not these two are different sides of the same coin, they sure are brewed in the same cauldron.

IVolunteer International is a 501(c)3 tech-nonprofit registered in the United States with operations worldwide. Using a location-based mobile application, we mobilize volunteers to take action in their local communities. Our vision is creating 7-billion volunteers. We are an internationally recognized nonprofit organization and is also a Civil Society Associated with the United Nations Department of Global Communications. Visit our profiles on Guidestar, Greatnonprofits, and FastForward.