How to make sure you don’t corrupt the authenticity of online activism or drive potential allies away from a cause, and how to create a more sustainable social consciousness.

Black squares. Hashtags. Callouts. Anyone with an active social media presence would have noticed the growing frequency and intensity of social justice and activism-related content in the virtual community over the last decade. Then 2020 rolled around, and a global pandemic shifted people indoors, boosted our contact time with screens, and ignited a whole new level of popular engagement. This surge fast-tracked the evolution of the digital activism landscape and turned it into an omnipresent force, now well and truly inseparable from our feeds.

If you’ve been a long-term devotee to a cause struggling to work its way into mainstream discussion, you might feel vindicated to see it suddenly in the spotlight. But you also might be wondering how much is for show and how much shows a lasting commitment to advancing its goals where it matters. And how you can tell the difference.

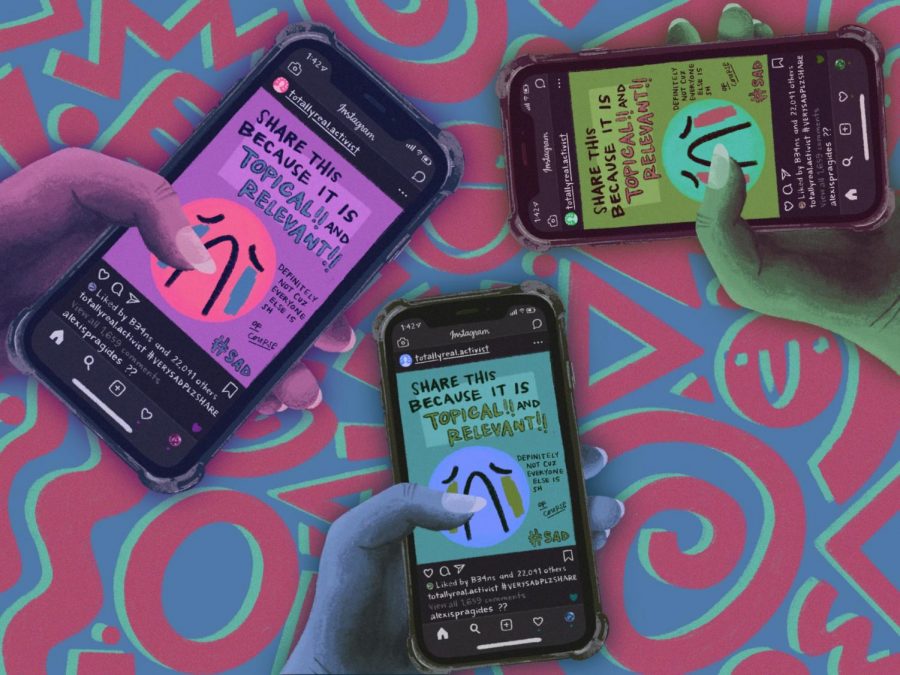

When a message is grabbed by individuals en masse, then churned out through at times millions of accounts in quick succession, it can become butchered and blurred. In this environment it becomes close to impossible to differentiate between those desperate to raise awareness and those seizing an opportunity to throw disingenuous support behind a movement they think will bolster their social currency and add sparkle to their online personality. The individualistic nature of social media lends itself to performance because of how it is structured. We attribute likes and views to value. It can easily become a promotion of ourselves, not the cause.

Performative activism is used increasingly as a term to criticize activism carried out, typically online, to inflate an individual’s social capital and image rather than for a genuine devotion to the cause or an interest in effecting actual change. It follows a similar line as the expression slacktivism, a negative label put on half-hearted attempts to support a cause through performing simple measures, like retweeting a sentiment, that require very little effort or commitment.

So, are we doing a good thing when we like a campaign’s Facebook page or tell our followers off for not speaking out about the injustices happening all around us? Are we a bad person for not using our online platforms to spread awareness or show our concern for the latest international crisis? Are we forcing ourselves to publicize superficial care because Samantha from high school told us we cannot call ourselves a good person if we don’t?

I’m not sure I can definitively answer these questions for you. But it’s certainly a conundrum worth contemplating.

You had my curiosity. But now you have my attention.

Before I make you too nervous about engaging in issues online or instigate a moral breakdown, it’s important to note that not all online activism is insincere or inherently bad. Individuals with the right intentions who understand how to appropriately and respectfully use platforms can create incredibly effective and informative content that spreads awareness and connects others to a cause.

Technology is now an essential and powerful tool on a social movement’s belt, bringing with it significant organizational benefits. Digital tools give a voice to the voiceless and facilitate the rapid mobilization of people on an immense, worldwide scale in real-time. They also allow people to support efforts they cannot attend due to geographical restrictions.

And clicktivism (another, less derogatory, rendition of slacktivism) gets an unfairly bad wrap according to a 2020 paper in the journal Science. The authors contend that research consistently indicates that “[d]igital political activities – including low-cost ones – are a complement to, not a substitute for, their offline counterparts.” This is backed up by another research paper laying out the current empirical evidence overwhelmingly suggests that online and offline activism are positively related. Another article argues that critics of online activism are still unable to discredit the vital role it plays in value alignment and the potential to ultimately lead to tangible action.

Climate strikes in 2018 inspired by Greta Thunberg utilized the speed of messaging and connectivity online and translated this into in-person rallies on the ground on an international scale. From 29 July to 28 August 2014 when the ‘ALS ice bucket challenge’ was in full swing, the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Association received $98.2m in donations. This was an incredible rise from the $2.7m donated during the same period the year before. And disability advocates expressed amazement over the rare widespread coverage and attention the disease received, even when others questioned the egocentric and celebrity show-off character the challenge took on at times.

“Not everyone is going to donate – that’s a shame. Not everyone who did donate will donate again, that’s to be expected. But the huge amount of extra money and publicity means it’s the charities that are benefiting.”

Joe Saxton, Director of Nfpsynergy

It is unclear whether the TikTok users who joined forces in an attempt to affect attendance numbers at President Donald Trump’s Oklahoma rally in June 2020 actually succeeded with the disruption. But according to Kelly Dittmar, an associate professor of political science at Rutgers University-Camden, it is irrelevant whether the rally itself was impacted. “It matters if it got some young people who wouldn’t have otherwise thought about this presidential election to think about it and to think about the implications,” Dittmar said of the online campaign. And her comments are seemingly substantiated by a survey of Americans on social media in June 2020 that showed 54% of users aged 18-29 said they had used their platforms in the last month to look for information about rallies or protests happening in their area.

Awareness is crucial. But awareness does not necessarily equate to actual change or a productive contribution. Online social spaces are cluttered with every cause imaginable. This can dilute the impact and meaning of certain movements. And if a cause needs real action, not just attention, it leaves much to be desired.

“Justice isn’t some weekly trend.”

Sophie Egar at TEDxYouth@PepperPike 2018

When the armed group Boko Haram kidnapped 276 Nigerian schoolgirls in 2014, the online tag #BringBackOurGirls quickly went viral and founded a global campaign demanding their safe return. Even with the explosive flurry of media attention and high-profile backings, six months later the concern for the captured girls had mostly fizzled out despite the fact that none had been rescued. Fast forward to today and, barring a small group of faithful campaigners, there is no movement to recover the remaining 112 who are still missing.

Our attention span is short. The perpetual stream of data, information, and news, and the way new events are sensationalized, means campaigns often simply ‘trend’ for a brief period before being brushed aside and replaced by the next big issue steamrolling through at high velocity. There’s a steady-moving conveyer belt of shocking injustices we need to act upon NOW. And it’s mixed up in everything else cycling through our online feeds demanding our comment and interest. Throw in some misguided reactionary posts and online shaming to the mix and you’ve got a bit of a problem.

Think before you impulsively click

Social media is an untamed beast, an enigma that probably understands us more than we understand it and its influence over us. “Social media is just plain ironic,” says James R. Bailey, professor of leadership at the George Washington University School of Business. “On the one hand it has unparalleled reach, making it tailor-made for activism. On the other hand, anyone can express themselves, without expertise, temperament, or even conviction. The result is that those of us who want to contribute are either lost in the mess or can’t tell what’s legitimate and responsible. Social media’s advocacy draws as many people as it repels.”

Sharing content with the click of a button because everyone else is without checking its source or helpfulness to the cause can trivialize the message, hinder progress, and reduce a serious movement to a temporary fad.

Many people may not be aware that the black squares that inundated social media platforms last year in June accompanied by #BlackoutTuesday were the result of misconstruing the original message of the #TheShowMustBePaused movement. Although unrelated to the already established #BlackLivesMatter movement, the two became accidentally conflated and actually hindered the ability of BLM personnel to distribute critical information to protestors on the ground.

This does not mean that people who posted a black box are bad people or were deliberately sabotaging. But it does illustrate the dangers of reflexive users who don’t take the time to inform themselves before knee-jerk posting.

Breanan Turner, a PhD candidate at RMIT University, reflects: “The #BlackOutTuesday black tile campaign on Instagram highlighted how powerful peer influence can be on social media in terms of not wanting to be seen as complacent and silent on a significant and very public social issue. Unfortunately, due to a lack of context and clear instruction, the campaign ended up muting very important #BlackLivesMatter content and Black voices.”

“It kind of makes me wonder how the Black Lives Matter movement would have played out this summer if we weren’t in a pandemic and if people weren’t forced to only experience the world through their screens.”

Amanda Maryanna

“Why are you not talking about this?!”

“[People ask,] ‘why isn’t anyone talking about this?’ as though all of us have the emotional capacity to hold the world and all the problems in the world, on our shoulders.”

Daze Aghaji

“If I don’t see you reposting, please unfollow me”

“Silence is violence/compliance”

When users scroll past post after post captioned like this, they might begin to feel the pressure that they too must make as much noise as possible. And what was once a way of highlighting inaction in real-life situations as complicit behaviour, has now been distorted in its application to our online voice. The barrage of shaming and guilt-tripping content may lead us to internally question, “am I really a bad person for not reposting every social justice meme?”

With all its potential, social media also unfortunately seems to have a tendency to twist well-meaning initiatives and turn people against each other. With the initial benevolent intention of cultivating social consciousness, online activism can morph into an unforgiving ethical minefield of showboating, toxic virtue signaling, and personal attacks.

In her article for i-D, Ella Glover points out: “Instead of seeing activism as a good thing, it has become mandatory; expected.” This is not to say that encouraging a sense of social responsibility, self-awareness, and compassion for those experiencing injustices is not on the right direction towards fostering a positive culture of global contribution. But how this is done will determine its longevity and legitimacy.

There is a suggestion that people just beginning to explore activism can be disheartened by being criticised for doing something wrong.

“Publicly shaming people who use social media for social change is not productive. Rather, we should focus that energy to encourage each other to be better people in our society.”

Prevail Laurent at TEDxUNB 2021

Shame might be a great motivator for large companies to make changes to appease consumers, but a company is not a human being and can better weather the storm of negativity. Conversely, public humiliation and fear of a life-long damaged reputation should they take one wrong step can be detrimental to an individual’s participation. And shaming someone for trying impairs their ability to attempt self-improvement, leading them to disengage, dig further into their beliefs, and support the status quo.

Glover describes the underlying sentiment of this kind of online toxic behavior is that if we aren’t publicly condemning something bad, or advocating for good on our platforms, we aren’t doing anything at all, and it doesn’t matter what we are doing in real life. But this is simplistic and ignorant of the multifaceted nature of activism. A lack of talking is not the mark of a lack of action. And the reality is that not everyone has the means or readiness to engage in social issues.

Those that are overly judgemental of online efforts could be driving away potential allies rather than hooking into a pre-existing, albeit perhaps minimal, interest to encourage more concrete engagement. There is a real opportunity to build on this interest in an inclusive and sustainable way, rather than investing all our time in moral conceptual debates over what constitutes a ‘real activist’.

At the Obama Foundation Summit in Chicago in October 2019, Barack Obama expressed concern over the dark side of ‘callout culture’: “I do get a sense sometimes now among certain young people, and this is accelerated by social media, there is this sense sometimes of: ‘The way of me making change is to be as judgmental as possible about other people. And that’s enough.”

“That’s not activism. That’s not bringing about change. If all you’re doing is casting stones, you’re probably not going to get that far. That’s easy to do.”

Barack Obama

I am not calling for the stifling of disagreements and debates. These are vital. Difficult and uncomfortable conversations are necessary and frequently a precursor to change. And that’s not to say that people should not be held accountable or be made aware of their mistakes, because that is how we grow and improve. But dialogue with a tone of moral superiority, righteousness, and disrespect serves no one, and is not conducive to open-minded listening or learning. “I think what differentiates a call-out from bullying is that it shouldn’t be about punishing someone for something they have done, rather it should be about establishing a new pattern of behavior,” says writer and activist Kitty Stryker.

Performative activism and progress are not mutually exclusive, and the fact that so many are thinking about it and evaluating the merits of some online actions could be seen more optimistically as evidence of a growing awareness and openness to do better.

Let’s get real

“I remember one time after posting an infographic, I received a message challenging whether or not I had legitimately read it through. It felt awful to have my integrity questioned. I wholeheartedly supported the message, and my efforts to endorse it were met with immediate criticism. But I’ve forced myself to take a step back and recognize that I don’t really have a right to be upset with the person questioning me. Wasn’t I, moments before, silently criticizing and questioning somebody else’s infographics?”

Eliza Walpert

With their aesthetic layouts, infographics, and condensed format, social media platforms allow users to sculpt information into eye-catching, punchy, mini chunks. This is not completely reductive, because of their accessibility and that they may engage and encourage further investigation. They work “because they are efficient and make complex information and issues digestible.”

But it doesn’t always work in the favor of particularly intricate issues that cannot be appropriately represented by a pretty, abbreviated, digital bite. And Amanda Maryanna asks: “Is it even appropriate to make activism aesthetically palatable.”

The world can be fatiguing and unforgiving. News and media marketed for shock value and reaction instead of information and education only exacerbate the mental drain. Holding an expectation that ordinary people must come up to speed with foreign geopolitical nuances surrounding complex, protracted issues, in a matter of hours or days, is onerous and unrealistic. Aptly put by John Metta, “[it] takes decades of practice to navigate these issues correctly, and even the greatest academics on a topic might make a misstep after a lifetime of such work.”

What does it all mean?

Are you thoroughly confused now? Eliza Walpert’s piece might articulate the turmoil you’re experiencing. Confusion is good. It means you’re thinking.

I’m an optimist at heart and I like to believe in the inherent good of people. So, while online activism might have a dark and performative side to it, and we still have a mountain of progress, education, and self-awareness to climb up, I think we are making a start. Change feels painfully slow when you are living it, particularly in the context of historically embedded beliefs and behaviors that aren’t going down without a fight. No one has all the answers yet.

For me, there are some key takeaways from all this.

Activism shouldn’t be a competition. It should be about individual growth and constant conversation. Deep time and money commitment is a privilege of those with adequate time and money. What we can feasibly do will be a matter of our own personal circumstances.

We should be encouraging everyone to give what they can when they can, whilst ensuring they are also ok in their own lives. Not compelling people to take part in hollow messaging out of fear of being called out as callous and selfish.

There is of course only so much media saturation and awareness before something more tangible should take place. “Performative activism cannot become a replacement for concrete action. If we decide to share something on social media to create awareness, then our activism cannot end there,” says Joaquin Zurita, writer for The Organization of World Peace.

There are also limitations with the format of online conversations. Words on a screen are subjectively interpreted by the person reading them. Tone and emotion can become distorted, and the message may be lost in translation. To circumvent these shortcomings and prevent meaningful engagement from descending into an ugly back and forth, dial back into your immediate surroundings. Have a mature and measured conversation in real life with your friends and family, those who know you and who are more likely to listen.

Understand the context of someone’s views if they are different to yours before being so quick to write them off and shut them out. No one is perfect but we sometimes forget this when we are so hellbent on proving people wrong to elevate our morality instead of understanding their mistakes and giving space for them to learn.

And most importantly, check yourself and think about how you use social media and online activism. Start with asking yourself why.

- Am I doing this just because everyone else is doing it?

- Am I doing this because I care or because it will make me look good?

- Am I informed and educated on this issue? Do I fully understand the background of the subject matter? Is the information from a credible source?

- Do I need to post this or comment on this? Is my input offering something effective to the discussion, or am I posting just to be loud?

- Have I evaluated my own thoughts, biases, and behaviours to see if I need to make personal changes to align myself with the message?

- And most importantly: am I encouraging us to unite or am I creating tension and division?

It’s the little things

The sensible truth is that not everyone is cut out to be a dedicated activist. We should instead look for how everyone can sustainably engage in practices that collectively make the world a better, more understanding, and compassionate place. Instead of stretching yourself thin and burning out from every problem demanding your investment and action, identify what speaks to you and focus on that. This doesn’t have to be extensive or even take place online. Start small. It’s the little changes we all make, in our own lives and communities, that add up big.

“Find a cause you love. It’s okay to just pick one. You are going to need to spend a lot of time out in the real world trying to figure out how to stop being a lost loser so one cause is good. But find one. And devote some time every week to it.”

Shonda Rhimes, Dartmouth Commencement Speech 2014

Sophie Egar talks about the importance of setting ‘ambitious but realistic goals’ in her TEDxYouth Talk. Goals such as eradicating human trafficking or halting human-caused climate change are noble but described by Egar as ‘too broad to be directionally actionable’ and virtually insurmountable for just one person.

If you are looking for a place to start, watch Amonge Sinxoto as she eloquently explores the essential landmarks in her journey of transforming social media into social impact. Do not be intimidated by her growing list of achievements already as a 17-year-old. The 4 points she discusses are applicable to any cause you choose to act upon, no matter the scale.

Not everyone can be a star activist operating on a high-level international scale with a laundry list of accolades and associations. And that is perfectly fine. In fact, it’s great. The world needs incremental change to be happening everywhere, especially at the grassroots level with small communities growing together and making their own little corner a better place.

This topic has many twists and turns and far too many aspects to be covered by one person’s thoughts on a page. But I hope this serves as a source of introspection and carries the discussion on as it will no doubt continue to evolve in the future.

IVolunteer International is a 501(c)3 tech-nonprofit registered in the United States with operations worldwide. Using a location-based mobile application, we mobilize volunteers to take action in their local communities. Our vision is creating 7-billion volunteers. We are an internationally recognized nonprofit organization and is also a Civil Society Associated with the United Nations Department of Global Communications. Visit our profiles on Guidestar, Greatnonprofits, and FastForward.