“Pride is a riot”

– Stonewall Inn

Pride, for so many of us, is a space of belonging. An enclave where we can be safe, sincere, and unapologetic of a reality still so often implicitly or explicitly censored around us. Pride offers resilience through community, support where there is so often rejection, and an example of a future.

Pride has come to signify a variety of things over its last half a century of history, yet in the context of 2020, we stand at a place where we are called to reexamine its conception, the meaning of its participation, and its significance. Amidst a pandemic, growing anti-LGBT sentiments worldwide, and a new wave of social rights movements, Pride 2020 has taken on a renewed meaning.

As a result, outlets from the New York Times to Vox, individuals, organisers and activists have posed the same question: What exactly does Pride mean now?

Unrest, belonging, and politics of Pride

LGBT+ history is a rich and multipolar story, with struggles around the world defining divergent trajectories and challenges for its local communities. However, the specific idea we have of Pride is a very recent phenomenon. The Stonewall riots gave way to our contemporary conception of Pride; with the first Pride march in 1970 born out of rightful anger, as a struggle against police violence and unjust laws. The marches and demands for equality the movement embodied grew, and would eventually spread globally; offering for many the first example of a collective, to challenge the isolation still so defining in queer identity. At its core, Pride has always been a political affirmation: that the LGBT+ community was anchored in a state of oppression, and this could no longer stand. But this shift did not occur in a vacuum. The 1960s in the United States were defined by massive social unrest and political upheaval within the context the Civil Rights movement. In fact, many have argued Stonewall would have never existed without the path set by the Black Power movement.

Consequently, many activists are regarding this year’s Pride as a salient moment in American LGBTQ history. With Pride developing in the midst of worldwide social upheaval, there has been a resurgence of the spirit of protest that defined the Stonewall riots. We must remember, this echo of the struggle against systemic racism is not a parallel fight, but one deeply imbedded at the core of our community. Indeed, Black Lives Matter, the organization turned global movement, was created by black LGBTQ activists. In 2020, Pride has meant a return to protest and political action, summed to the struggle in solidarity with those suffering from the endemic terror of systemic racism.

Pride 2020: A pride with no parade

Pride month, and more specifically events organized around this theme, stand as an embodiment of spaces of self-expression, acceptance and celebration of identity; which for most of the year remain online or in very small circles. Nonetheless, this year the COVID-19 pandemic will requisite a change, making Pride a global online event; held under the call of “exist, persist, resist”.

Of course, this has not been the only gathering affected, and the spirit of community will still be the central element of this online congregation. Pride has not vanished. Yet, there is a sense of loss of something intangible when we can’t meet. This is because, as Allison Hope brilliantly states in her CNN article, “Pride is a feeling, not merely a parade. It is a long-fought, hard-earned prize produced by a community and the momentum we have created together. It is available for the taking by those coming of age who should know that they are loved and have a shot at a bright future, even if it doesn’t feel that way right now”. There is a physicality to this feeling. A sensation that is defined by stepping into a mass of people like yourself after a period of prolonged isolation or misunderstanding; one that for many LGBT+ people may have represented a majority of their lives. A feeling that while different in each individual, I believe can strike a chord in all of us.

So, while parades and physical spaces aren’t preconditions for the existence of a sense of cohesion and belonging, the loss of the visibility and validations these spaces offer can be recognized as a cost we will incur. In part, because even beyond our community, these displays of visibility have generally proven to be fundamental for advocacy efforts and movements towards more accepting societies. The idea of being out and proud creates real repercussions through the recognition it enables from public opinion, political leaders, and legislatures.

Organizers of this Global Pride event have expressed their understanding that this year’s Pride gathering will not be able to truly echo the experience of the live celebrations. Yet, there is a silver lining: a hope that the online nature of this year’s Pride will enable LGBT+ individuals in states with actively hostile contexts, or criminalising laws on sexual orientation, to fully access Pride for the first time.

A global perspective on struggle: LGBT rights across the globe

A Global Pride event necessarily reminds us of the vast differences of conditions affecting the community. As we have mentioned, LGBT+ history is a tumultuous struggle with many narratives. Even today, there are stark differences in the treatment and protections afforded to members of the LGBT+ community across nations. With this, we come across places where we can be recognised, and face relatively little discrimination, to others that maintain the death penalty for sexual orientation.

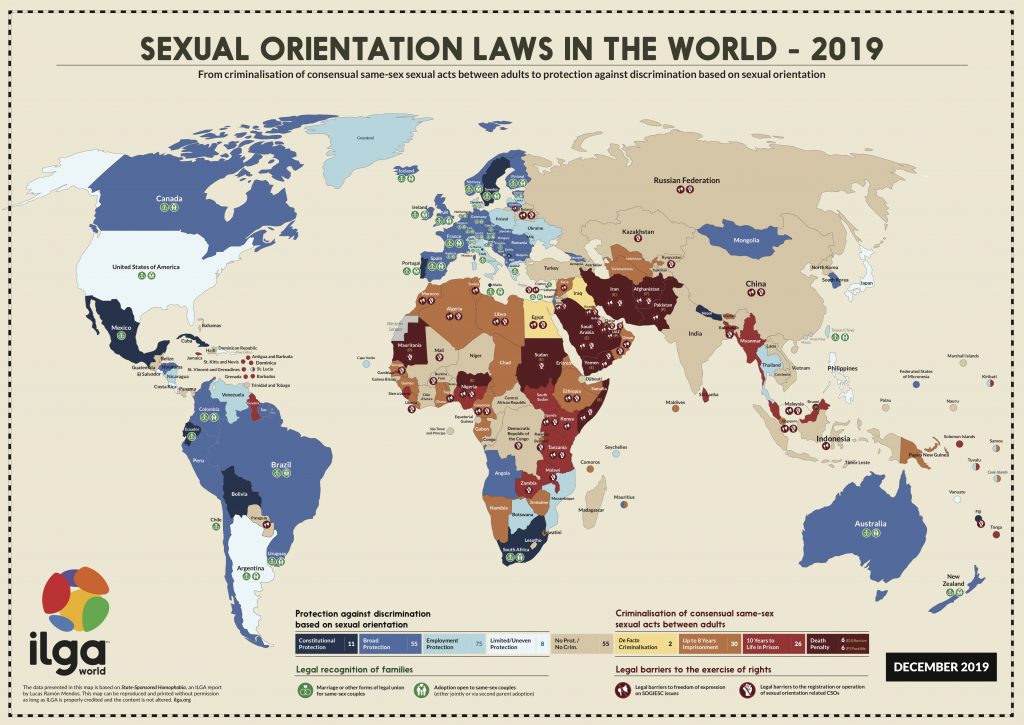

ILGA, the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, presents this situation through world maps that reflect sexual orientation laws in each country, along with the development of its famous State-Sponsored Homophobia report.

Map of laws on sexual orientation across the globe

These resources represent not only a visual demonstration of the profound inequality LGBT+ people experience across the world, but serve as a tool for human right activists, evidencing both the arbitrariness of persecutory laws, and the blatant lack of protections set forth to safeguard LGBT+ rights. Thus, despite increased globalization and global human rights movements, the great divides LGBT+ people experience around the world persist, and have come to be defined by a fracture along the “pink line”.

The pink line phenomenon

In recent decades, we have seen the emergence of a global debate on sexual and gender identity; a conversation which has now come to describe the world along new lines. The rapid expansion of the LGBTQ+ rights movement has effectively mobilized individuals across all regions, encouraging these actors to claim political identities and demand space and protection for themselves. As happens often when new collectives demand equal rights, there has been an emergence of a panicked resistance. Even in our globalized world, as human rights movements drove same-sex relationships and non-binary gender identities to be recognized and respected in some areas; polar opposite movements pushed for their criminalization and exposure to social violence in others. This barrier has come to be known as the “pink line”, separating those places steadily working towards the inclusion of the LGBT+ community, and those redoubling efforts to push back.

Yet this “pink line” is not as easily defined as national boundaries, and fluctuates as a result of social protest or attempts of political power play. This line is often leveraged by politicians seeking to gain power, through support for traditionalist notions of family and nation, and what they consider pollutes those ideals. Notable manifestations of this are evident with Putin’s policies in Russia and Bolsonaro’s narrative in Brazil, among others. In addition, the information revolution has set a micro-version of the pink line within the lives of LGBT+ individuals themselves, who strain between liberal acceptance in online spaces and heavy constraints often set in the workplace and family.

We can affirm the LGBT+ movement remains a multipolar struggle, ranging from the fight to guarantee the most basic freedoms and protections, to attempts of moving from legal equality to real equality. But these differences should not be seen as fractured realities. While the struggles LGBT+ people face are divergent, any amount of progress will serve to exemplify what can be achieved, and what will eventually become the objective somewhere else. The pink line is defined by shades of continued oppression and hardship, but as all other human rights struggles, the endgame is for the line to disappear as positive rights and protections emerge– the pink line can fade slowly out of existence, nationally and individually.

Where we stand, where to go

In 2020, we cannot stand at Pride as we often would. But this does not nullify the impact it holds for those that cannot be themselves or exist in peace under fear of violence or rejection. The sentiment Pride represents for the community remains one of hope, celebration, and resistance.

This year, Pride calls back to its spirit of protest in tandem with Black Lives Matter.

This year, Pride opens the first global and virtual call for resilience and belonging across the globe.

This year, Pride refuses to dissolve under isolation, and continues to fight for visibility.

This year, Pride still seeks to erase the pink line in favor of real equality.

This year, Pride changes, but it continues to exist, persist, and resist.

Sources

Brown, J; Machado, C & McBee, T. (2020). What Does Pride Mean Now?. New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/16/arts/author-gay-pride-2020.html

Burns, K. (2020). What will Pride mean this year?. Vox. Retrieved from: https://www.vox.com/2020/4/29/21227999/online-pride-coronavirus-pandemic

Hope, A. (2020). Pride is a feeling, not a parade. CNN. Retrieved from: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/05/31/opinions/gay-pride-during-pandemic-hope/index.html

Global Pride (2020). Retrieved from: https://www.globalpride2020.org

Gevisser, M. (2020). The Pink Line: Journeys Across the World’s Queer Frontiers

Pruitt, S. (2020). How the Black Power Movement Influenced the Civil Rights Movement. History. Retrieved from: https://www.history.com/news/black-power-movement-civil-rights

Salzman, S. (2020). From the start, Black Lives Matter has been about LGBTQ lives. ABC News. Retrieved from: https://abcnews.go.com/US/start-black-lives-matter-lgbtq-lives/story?id=71320450

Tóibín, C. (2020). The Pink Line by Mark Gevisser review – the world’s queer frontiers. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/jun/20/the-pink-line-by-mark-gevisser-review-the-worlds-queer-frontiers

Roy, J. (2020). Pride began as a protest. In 2020 in L.A., it will be again. LA Times. Retrieved from: https://www.latimes.com/lifestyle/story/2020-06-04/how-to-celebrate-pride-2020-coronavirus-protests

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of IVolunteer International.

IVolunteer International is a 501(c)3 tech-nonprofit registered in the United States with operations worldwide. Using a location-based mobile application, we mobilize volunteers to take action in their local communities. Our vision is creating 7-billion volunteers. We are an internationally recognized nonprofit organization and is also a Civil Society Associated with the United Nations Department of Global Communications. Visit our profiles on Guidestar, Greatnonprofits, and FastForward.