As I was writing this article, the news about my collegemate’s demise hit me via WhatsApp. That he had committed suicide after a long struggle with mental healthcare was a hard pill to swallow. On 13th September 2021, a doctor from Guntakal, Hyderabad, chose to end his life after a long-drawn battle with depression. He was a general practitioner at the Agra Military Hospital. The loneliness and distress catalyzed by the pandemic engorged upon him and he succumbed to suicide.

A close family friend, with whom I shared a lifetime of memories, had contemplated suicide throughout last year. He had to combat an enormous financial crisis due to the pandemic and subsequently, anxiety. Last month, he suffered a fatal heart attack at fifty-five years of age, leaving his kin and kith regretful for not having reached out to him earlier. Last year, I also received numerous calls from friends, who wanted to connect to a psychologist or mental healthcare professional.

On one hand, I remember feeling rather content at the promptness this generation was showing toward addressing mental health issues and reaching out for help. On the other, I was brooding about the million others in my country who don’t know why they’re suffering. These are people who don’t know that mental healthcare is a real thing! This is precisely why it is high time to give due attention to India’s mental healthcare epidemic.

The Man who put Mental Healthcare on India’s Map

At this juncture, I respectfully remember the phenomenal Mr. Keshav Desiraju IAS who served as the union secretary with the Ministry of Health. He was the harbinger behind the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017. The act officially decriminalized attempted suicide and sought to extend mental healthcare support for those who were in need. This was a progressive move on the nation’s part which safeguarded patients from possibly exploitative family members and caregivers. Mental wellbeing finally made it to the mainstream health narrative.

Desiraju’s demise on the 5th of September 2021 is lamented by a nation that did not hitherto know that mental healthcare is their fundamental right. His association with the WHO vouching to pass resolutions for mental healthcare provision in India brought this imperative to the limelight. All his initiatives are of utmost importance to the future of India’s youth and health. However, the implementation lag between theorization and execution is slightly different for a nation as diverse and large as India. This is where the disparity between a utopian idea and painful reality is rather appalling.

Mental Healthcare and India

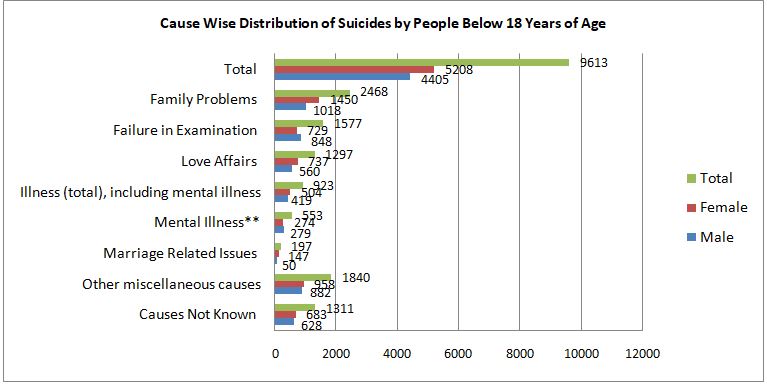

India is the second-most populated country in the world. Going by the WHO’s 2018 reports, it is the world’s ‘most depressing country’ too, with 36% of its population admitting to combatting depression. Out of 149 countries, India is at 139 in the World Happiness Index. The National Mental Health Survey of India (2015-16) recorded that 10% of adults were fighting a mental health condition including anxiety disorders and depression. According to the Global Burden Disease Study 1990-2016, India accounted for 36.6% of all deaths by suicide in women across the world and 24.3% in men. Suicide is the leading cause of death among the youth of the country.

My little state down the south of India, Kerala, devastatingly records the fifth-highest rate of suicides in the nation with 24.3% which is higher than the all-India rate of 10.2%. These statistics are only garnering speed in the backdrop of the ongoing, stubborn pandemic. The number of suicides among children (<18 years of age) hiked up to 173 in the first nine months of 2020. My hometown of Palakkad, the largest district in Kerala, topped the list with 23 student suicides. According to the State Crime Records Bureau, the rate of suicide among girls was also more in 2020. In India, there are about three psychiatrists for each one million people! In the US, this is 14,000.

The stigma around mental health in India is a long-processed system of beliefs, customs, and dogmas. There are prescribed ways to feel ‘normal’ in our society. Anything slightly out of the norm is questioned, regulated, and forbidden. More often than not, it is the chaos behind the ‘normal’ that goes unnoticed. One in every twenty people in India suffers from depression. This grim picture is shielded away from the public eye because mental illness is recurrently equated with madness in the country. The advent of the technologically sound era has helped many a person from the peripherals to open up, whilst maintaining their anonymity. This, however, is a small demographic of people who have access to the internet and gadgets.

Anything that’s human is mentionable, and anything that is mentionable can be more manageable. When we can talk about our feelings, they become less overwhelming, less upsetting, and less scary.

Fred Rogers

Dr. Shyam Bhatt, India’s leading psychiatrist, in a panel discussion on NDTV in 2017 regrets how we are still compelled to talk about shame and stigma surrounding mental health. We haven’t even got that far as to improving our mental healthcare infrastructure. We’re still stuck at palliating the symptoms instead of offering comprehensive care. And every time there is a ray of hope in the form of government or media interference, they tend to fade out without real implementation.

Hinderances on the Way

In August, I had decided to conduct a survey-based analytic study on the mental health crisis among adolescents in Palakkad. This was part of a scholarship offered by the Directorate of Collegiate Education. I met with a lot of skepticism and internal dilemma during the course of this research. Nevertheless, I ardently believed in this project. I was earnestly looking to make a change. I was not entirely sure what I was getting into and was hoping to learn on the way.

Young adults in India have the ability and means to reach out to mental health professionals and counselors. The adolescent group, however, was still heavily dependent on their parents, with little to no autonomy over their decisions. That mental health is taboo in our society, especially in the rural areas, only added to this gap between the help and those who needed it. India is still struggling to dispense an all-embracing healthcare facility to all its citizens alike. Venturing into a sensitive issue like mental healthcare, especially amidst a pandemic, is supposedly a far-fetched dream. Less than 1% of the health budget of the country is allotted for improving mental healthcare infrastructure and recruiting an efficient brigade of professionals. Also, insurance does not cover mental health requirements.

Are we Doing Enough?

Dr. Arun B. Nair, a psychiatrist from Kerala observes that systematic counseling and therapy can help mitigate the emptiness that has engulfed our society which can result in crimes sprouting from loneliness, anxiety, and financial difficulties, such as domestic violence, alcohol, and drug abuse, etc. In this regard, the solution to this conundrum is rather simple. However, nurturing public awareness and offering effective assistance are mammoth tasks. This is precisely why, in spite of having many outreach programs like the Dial-a-Doctor initiative by DISHA and the District Early Intervention Centers (DEIC), Lifestyle Education and Awareness Program (LEAP), Our Responsibility to Children (ORC), and the Gurukulam Project, much of the population still remain in the dark as to being aware of the reality of mental health illnesses. Such initiatives are seldom evaluated after their commencement.

Three losses dominate the mental health systems narrative: dignity, agency and personhood. Far-sighted changes in policy and laws have often not taken root and many laws fail to meet the international human rights standards. Society’s responses are often based on conditioning and perceptions, often verging on visceral forms of prejudice.

Vandana Gopakumar & Keshav Desiraj, The Hindu (July 07, 2021)

According to Dr. Ramkumar G. S., Psychiatry Specialist, Caritas Hospital, Kottayam, each of such student-centric interventions needs to be assessed for their effectiveness. He identifies this as a major research gap. Also, he critiques the lack of rigor in carrying out the objectives of these interventions. Additionally, there is a lack of clarity in their mechanisms of delivery. It is rather upsetting to note that none of these programs could deliver an affirmative evaluation report. It is, however, some solace to learn that the state is waking up to the need of the hour via baby steps at a time.

The Adolescent Dilemma & the Lack of Penetrative Freedom

My research was conducted remotely, by circulating Google forms to different schools to collect data. This was, of course, due to the ongoing lockdowns the state was facing. Trying to collect data via smartphones and gadgets limited my respondents to those who have access to such amenities. It helped that much of the academic transfer was carried out virtually because the circulation of the form was easy. However, there is very little penetrative freedom into the school systems in Kerala. In order to convince an administrative officer of a school about the importance of a sensitive survey like this one, I had to spend days issuing request letters and waiting for a sanction. The condition in the colleges of the state is definitely a lot better. Students have a tad bit more liberty to personally indulge in such initiatives without awaiting permission.

I made sure to allow respondents to maintain their anonymity during the survey hoping to receive the most honest answers. Since many students may be using the phones of their parents or relatives to fill in the form, they could have felt hesitant to be candid. This was another very important aspect of mental healthcare in India which upset me. The District General of Police (Trivandrum Rural) R. Sreelekha, in her report on student suicides in Kerala, noted that the majority of cases remain unknown to the families of the victims. There is much diffidence for opening up, usually in fear of being misunderstood. As part of my study, the impact of the year-long lockdown was scrutinized. It brought back distressing answers about the lack of socialization and its impact on young minds. The over-indulgence in mobile phones, video games, and the internet rendered their lives monotonous and depressing.

Disheartening Results

My survey was based on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CED-D) for the target group of students of fifteen years and above. During the course of the survey, the responses made by young adolescents substantiate how they have been, as a generation, suffering under the stronghold of these unprecedented times, often combating the inability to open up to others. I made the conscious choice of picking both public and private schools to reach out to a heterogeneous group of students, from different facets of society.

24.6% of students verified that they were fighting gloom and despair. Nearly 50% of them fought the inability to open up, feeling insignificant in comparison to those around them. 15.7% of the students felt like failures and 27.6% of them communicated very little with their families. Many students attested to combating the lack of interpersonal communication and familial constraints. The financial difficulties many families faced during the pandemic also had their effect on children; many of them confessed that online classes were hectic, ineffective, and expensive. The pandemic also served additional pressures of loneliness.

The objective of my research was to bring out the inconsistency between what’s on paper and what is factual. The government of Kerala had issued a project in 2020 in association with the Education Department and the Women and Child Welfare Department to extend help to students who are suffocating under stress, depression, anxiety, and behavioral dilemmas. This project was to be implemented via school counselors and phone-in assistance. However, very little investigation and follow-up have occurred in this regard. It is a pity that the most literate state in India is struggling to tackle a mental health pandemic.

Why Such Pain, India?

Coronavirus has taken a toll on the global community. Every person fights their own demons and no story is less heartwrenching than the other. There have been many studies evaluating the psychological impact the pandemic has been having on India. It is almost as though the country was waiting for this catastrophe, to spare an ear to its psychological ailment. India has been a depressed nation long before the pandemic. According to Neharika Rajagopalan, the Mental Wellness Advocate and Development Professional and the founder of DESHA DHWANI (an initiative seeking to dismantle the stigma surrounding mental health), this country which is gearing up to be the fifth-highest economy in the world is also home to 600 million youth. She observes that the chase of financial advancement has been hard on India’s youth because more often than not, they do not realize at what cost are they chasing success.

The WHO declares that there is an 80-86% of treatment gap for depression and other suicidal mental ailments in India. Ms. Rajagopalan also notes that the country is unwilling to fathom the real gravity of the issue. This is also because a large demographic of the population is still confined to rural spaces, deprived of basic healthcare and knowledge. For the young, especially, loneliness is cited as the leading cause of depression, reveals studies. Young Indians have been battling the burden of expectations for a long time. The collective consciousness of the country castigates individual pursuits for the most part. Although this might be too much of a generalization, the Indian community does thrust orthodox pressures over the young. According to a survey conducted in 2019, 93% of students were only aware of seven career options, those that have been sanctioned and licensed by the society as ‘white-collar’ professions. This is the story of a country whose average age is a fruitful 28.4 years as of 2021.

Nevertheless, credit when it is due; India is slowly taking the high road. The transition from joint families to nuclear ones has helped many young people to pursue what they really want, with minimal pressure from households. Parental anxiety is taking a backseat these days. The change is slow. However, upper to middle-class parents are loosening the clutches around a six-figure salary for their children. If anything, the children are learning to normalize their passion and rebel for causes that determine their individuality. The power of social media cannot be dismissed here. With the popularity of these platforms, people have begun to find a space to open up. The talking cure is clearly very efficient.

If such provisions may be extended to the rural landscapes in India as well, miraculous changes may be observed. The young, the women, and those of marginalized groups can be pulled back from the edge over which they are currently living, trying to make sense of the pressures they are subjected to. Sure enough, the problem must be tackled at the root. I believe we should start with ending the train of burdensome responsibilities that make up the growing years of a child. Responsibilities should ideally start with being kind, to oneself and others. With less societal and familial interference in the creative vigor of a child, we could guarantee a community of unique talents and flair.

The Way Forward

During my research, I found it extremely hard to have one-on-one conversations with students. This deprived them of an opportunity to open up. Many students I’d approached directly also shared the impracticality of the survey since they do not own smartphones or have family members who own them. However, every time I made an effort to reach out to a person, there was an earnestness that was reassuring. I realized that people are actually looking for ways to unload their emotional baggage, if only they get the provision.

All it takes to combat India’s mental health epidemic is an open mind. That is surely a good place to start. Once the stigma wears off, the path to improvement is rather clear. With such potent manual capital, a country like India should not have to struggle to feel happy and be productive. So if we could loosen the ties around our minds a bit, it could go a long way. This is not an impossible task. In fact, it is a tad bit easier than fighting COVID. With a bit of willingness and cooperation, we could put to rest many a dogma.

Sure enough, the interventions from the government and the healthcare sector should be promoted, augmented, and improved. The youth can do much about safeguarding the nation’s mental health. Here is where the significance of volunteering comes into the picture. If the young could have gained this country its independence in 1947, there is nothing young India is incapable of. It felt like a warm hug to me when I learned that numerous studies had been carried out last year regarding the mental health wellbeing of India. Each of these could draw more attention to this predicament we are fighting today.

If you are reading this and are looking to make a change, know that it’s never too late. I ventured into this study as a fresher. With the information that hit me during its course, I was at least able to connect a few of those who are in need of help to mental healthcare professionals.

No change is small. It is often the tiniest of changes that could transform the world for the better. Start today by reaching out to your loved ones. They might have been waiting for you.

IVolunteer International is a 501(c)3 tech-nonprofit registered in the United States with operations worldwide. Using a location-based mobile application, we mobilize volunteers to take action in their local communities. Our vision is creating 7-billion volunteers. We are an internationally recognized nonprofit organization and is also a Civil Society Associated with the United Nations Department of Global Communications. Visit our profiles on Guidestar, Greatnonprofits, and FastForward